Please note: this Bulletin is being put on the website one month after publication. Alternatively you can receive the Bulletin by email as soon as it is published, by becoming a member of the Lewes History Group, and renewing your membership annually.

- No August Meeting

- Church Lane development (by Robert Cheesman)

- The origin of Cuilfail

- Who was Gundrada de Warenne?

- Parliamentary Practices (by Chris Grove)

- A Trade Token issued by John Draper of Lewes

- Malling Deanery

- An Edward Reeves portrait in the National Portrait Gallery collection

- The Salvation Army in Victorian Lewes

- Lewes Railway Photographs (by Anonymous)

- Lewes in the 1950s: how to qualify for a council house (by Chris Taylor)

- Mick Jagger in Lewes Prison

- No August meeting

We shall be taking our usual August break, so our next meeting will be on Monday 11 September when Mary Burke will speak to us on the importance of the River Ouse for the growth of Lewes.

- Church Lane development (by Robert Cheesman)

I have two points to add to the interesting article on ‘How to tackle a housing shortage’ by Chris Taylor in Bulletin no.156.

When the south side of Church Lane was being developed in the 1950s the milk distribution business situated at the junction of Church Lane and The Martlets remained there for some years. The current flats on this site were not put up until after the business closed. I can’t recall exactly when this happened but think it was in the 1960s.

The two bungalows pictured on the north side of Church Lane were built at a later date than the other houses on this side of the road. Whether they were originally intended for the Police I don’t know but the family who have been resident in the western one from an early date could no doubt provide details.

- The origin of Cuilfail

The Cuilfail estate was built on land owned by solicitor Isaac Vinall, a stalwart of Jireh Chapel, where his father and grandfather (both John Vinalls) had been ministers. Cuilfail was reportedly named after the Scottish village where his family spent their summer holidays. Google fails to locate any such village, though there is a Cuilfail Hotel near Oban.

The name Cuilfail means, in Gaelic, ‘sheltered corner’ so is perhaps not entirely appropriate for this particular Lewes site.

Source: Jeremy Goring, ‘Burn Holy Fire’ (2003) p.136

- Who was Gundrada de Warrenne?

Gundred or Gundrada de Warenne was the first wife of William de Warenne, one of the chief supporters of William the Conqueror, who fought with him at the 1066 Battle of Hastings. She married William de Warenne before 1070. Her husband was richly rewarded for his loyalty to the new Norman king. William de Warenne’s vast new English estates sprawled across many counties, but the two principal homes he built were Lewes Castle and Castle Acre in Norfolk. William and Gundrada were joint the founders of Lewes Priory, modelled on the great Abbey of Cluny that they had visited on an intended journey to Rome.

Gundrada bore William several children, including his successor the second William de Warenne, and died in childbirth at Castle Acre in 1085. Her body was however interred at Lewes Priory. Three years later she was joined at the Priory by her husband. He was created Earl of Surrey by William Rufus, who inherited his father’s English kingdom, and had by this date married again. William de Warenne, a Norman military leader for over 30 years, died of wounds sustained fighting for King William II at the battle of Pevensey, part of a quarrel between the new King and his elder brother Robert, who had inherited their father’s Normandy dukedom.

Gundrada bore William several children, including his successor the second William de Warenne, and died in childbirth at Castle Acre in 1085. Her body was however interred at Lewes Priory. Three years later she was joined at the Priory by her husband. He was created Earl of Surrey by William Rufus, who inherited his father’s English kingdom, and had by this date married again. William de Warenne, a Norman military leader for over 30 years, died of wounds sustained fighting for King William II at the battle of Pevensey, part of a quarrel between the new King and his elder brother Robert, who had inherited their father’s Normandy dukedom.

Gundrada and William’s remains were buried in lead cysts, fortuitously rediscovered when the new railway line was driven through the site of the former Priory in 1845. Her grave was covered by a magnificent carved tombstone, discovered in Isfield church in the 18th century, where it had been re-used in the memorial to a local gentleman. The cysts and the tombstone are now reunited in the Victorian chapel built to their memory at Southover church.

Image is a chalk lithograph of the cysts by Frederick William Woledge, based on a drawing by Richard Henry Nibbs.

But who was Gundrada? The Priory monks claimed that their founder was William the Conqueror’s daughter, step-daughter or adopted daughter. She was perhaps a member of his Queen Matilda’s household – there is a surviving charter by which Matilda gave Gundrada a Cambridgeshire manor that Gundrada later gave to Lewes Priory. However, Victorian scholarship concluded that she was no blood relation of either William the Conqueror or his Queen, but instead from a Flemish family associated with the Normans.

Her elder brother Gerbod was made Earl of Chester by King William I after the Conquest, but soon returned to Flanders. His later history is uncertain, but one story is that he became a monk at Cluny. Another brother, Frederic, with whom Gundrada according to Domesday held English property even before 1066, was also awarded Saxon estates in Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire after the Conquest. Frederic was killed in 1070 by the Saxon rebel Hereward the Wake, leading William de Warenne to become one of his most enthusiastic pursuers. Gundrada inherited the estates of both her brothers, so became a wealthy woman in her own right.

Sources: Wikipedia; Sharon Bennett Connolly, https://historytheinterestingbits.com/2016/07/30/gundrada-daughter-of-debate/; the image of the cysts is from the Wellcome Collection

- Parliamentary Practices (by Chris Grove)

In its 28 January 1793 edition the Hampshire Chronicle continued its review of the means by which the different local boroughs each entitled to send two members to Parliament decided who should be their representatives. In this edition they covered three Sussex boroughs, Horsham. Midhurst and Lewes. The information was taken, without attribution, from the 1791 Universal British Directory, but one of the Directory compilers was the proprietor of the Hampshire Chronicle.

In Horsham there were 25 burgage holders who made the decision, but they were all in the hands of two members of the landed gentry (one the Duke of Norfolk). There were 125 burgages in the historic borough of Midhurst, but none of these included any houses, as the town had moved since its incorporation. The Earl of Egremont had purchased the estate that included the now-empty burgage plots for 40,000 guineas, so whenever an election loomed he appointed his trusted nominees as their holders, and at the last election they had returned to Parliament two of his brothers.

At Lewes things were, by comparison, almost democratic:

Editor’s note: While Thomas Pelham-Holles, Duke of Newcastle (1693-1768) did indeed exert every effort to influence who Lewes (and many other Sussex boroughs) sent to Parliament for over 40 years, the Hampshire Chronicle rather overestimates his control. The interests of the Pelhams and their Whig allies in the town were substantial, but Lewes voters had minds of their own. There were also other, Tory, interests at work. Usually sufficient Lewes householders could be bribed, cajoled or bullied for the Duke’s candidates to be returned but, unlike the rotten boroughs such as Midhurst and Seaford, Lewes could never be taken for granted. A successful Lewes campaign could cost the Duke, his allies and sometimes the candidates themselves a small fortune. The state paid too, as some of the votes were secured by the promise of government positions for the voters or their relatives. Government sinecures with high salaries and few duties were particularly prized, but also at stake were quite modestly-paid government posts involving actual work, such as carpenter’s jobs in the Royal Navy dockyards.

All the emphasis during the election campaign was on securing the promise of an elector’s vote. An Englishman’s word was his bond, and once a promise had been given it would be kept – as illustrated by Thomas Hay’s success in 1768 (the year of Newcastle’s death). There was of course no secret ballot at this date – voters declared their votes in public before the returning officers, and who had voted for which candidate was recorded in a poll book published after the election. There were, however, dirty tricks. It was not unknown for opposition voters to be entrapped by drink and then effectively imprisoned in a distant inn until after the poll had closed.

- A Trade Token issued by John Draper of Lewes

Another Lewes trade token from the mid-17th century was recently offered for sale on ebay. This one was a farthing, and rather more crudely made. One side shows a lion rampant with the inscription round the rim ‘JOHN DRAPER IN LEWLS’, with the second E of Lewes replaced by an L. Several other John Draper farthings found online all have this same error. On the other side are the initials of John Draper and his wife and the inscription ‘BY THE MARKET PLACE’. Unlike other Lewes and Cliffe tokens issued by Mary Akehurst (Bulletin no.135), Ambrose Galloway (no.116), Edmund Middleton (no.132) and Richard White (no.113) shortly after the Restoration, this example does not carry the date it was issued. Colin Brent in ‘Lewes House Histories’ has John Draper, a scrivener and licensed victualler, as resident at 60-62 High Street in 1655, 1662 & 1665.

The illustration shows a similar token from the British Museum collection, item T.5373.

- Malling Deanery

This postcard by an anonymous publisher, offered recently on ebay, shows a view of Malling Deanery and South Malling church, taken from the land on which Riverdale has since been built.

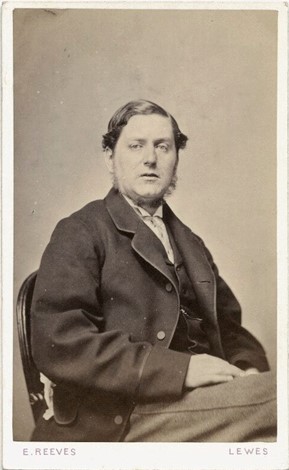

- An Edward Reeves portrait in the National Portrait Gallery collection

There is one photograph by Edward Reeves in the major national collection of portraits maintained by that great British institution the National Portrait Gallery. It is an albumen carte de visite thought to date from about 1865 that features as the sitter Walter John Pelham, the 4th Earl of Chichester (1838-1902). In 1865, when known as Lord Pelham, he was elected MP for Lewes in the Liberal interest. He retained that post until 1874, when he was replaced by the Tory William Langham Christie of Glyndebourne. In 1886 he became the 4th Earl of Chichester on the death of his father, and thus acquired a seat in the Lords. He died in 1902, aged 63, at Stanmer House where he had been born. He married but had no children, and was succeeded by a younger brother.

You can explore the National Portrait Gallery collection at https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/.

It includes thousands of works of art, ancient and modern, and photographs from all eras. Only a small selection can be on display at any one time at the Gallery, immediately adjacent to the National Gallery in Central London, so the online catalogue serves an invaluable role in making much more of the collection accessible.

- The Salvation Army in Victorian Lewes

In 1878 William and Catherine Booth changed the name of the evangelical pro-temperance mission church they had established in London’s East End to the Salvation Army. Their uniformed supporters held military ranks and began to expand their activities from the capital. Unusually they gave women officers equal status in the leadership with men (though not equal pay). In many places, especially those where brewing was an important local industry and Bonfire Societies were influential, they met vociferous and violent opposition throughout the 1880s, especially from a riotous opposition group known as the Skeleton Army. There were violent mob confrontations, often with the tacit support of local businessmen and sometimes the established church, in such hotspots of discontent as Exeter, Honiton, Worthing, Torquay and Chipping Norton.

The last major riots between the two armies (a little one-sided, as the Salvationists rarely fought back against the violent assaults on their men and women) took place in Eastbourne in 1891 and 1892, where the mayor led the opposition. He introduced a ban on their processions, enforced both through the courts over which he presided and by the violence of the Skeletons. Both armies drafted in supporters from elsewhere. Most of the Salvationists convicted of breaking the mayor’s by-laws, which they ignored, were fined, and when they refused to pay the fines imprisoned as an alternative. Lewes was of course the local prison, so it was to Lewes that the first four victims, three men and a woman, were sent in June 1891.

While their comrades were in the prison other Salvationists, many women with children, gathered outside to sing hymns and pray. When the four were finally released they were met at the gates by comrades from Eastbourne, Brighton, Newhaven and Tunbridge Wells. One of their number announced he had spent his term praying for the Eastbourne mayor and the hostile Lewes prison chaplain while the woman, laundress Louisa Clark, reported she had found black beetles in the prison blankets and maggots in the food. They were given a breakfast of ham and eggs at the home of a local supporter (very welcome after the prison fare of bread, gruel and water), and a few days holiday in Brighton before returning home to Eastbourne. There they were met by a huge crowd of Salvationists who had arrived on special trains, and participated in a huge procession about Eastbourne led by the Booth’s son Herbert on horseback.

Shortly before these events, in May 1891, a large Salvation Army van had passed through Lewes on its way to Brighton, and then it returned to Lewes two days later. This was one of the Army’s six ‘mobile forts’, and it parked on a green at South Street, where a great meeting tent was erected. The advance guard from the ‘fort’ marched to the railway station, where they met Salvation Army troops arriving from other parts of Sussex. The detachment was led by a courteous young man called Captain Whinneragh. They held well-attended services that included the novelty of a woman preaching, and 350 children accepted the invitation to tea. There was some noisy opposition, and a few violent attacks, but perhaps much less trouble than might have been expected in a town with a strong brewing industry and a proud history of Bonfire. They were still at their ‘barracks’ on South Street in 1893 (when they celebrated their anniversary with a weekend of well-attended services) and in the 1899 Kelly’s directory which notes ‘Salvation Army Barracks, South Street (iron)’. Thanks to the growing appreciation of the Salvation Army’s good work for the poorest of the poor and the lowest of the low, and to a more compromising approach to their street parades, opposition tailed off substantially in the 1890s.

I have then found no further references to the Salvation Army in Lewes until the 1930s. They had a Salvation Army Hall at 22 Eastport Lane in 1934 & 1938, in a building that had in 1927 housed the Sunday School of St Barnabas Church. In the 1940s, moved to St John’s Street, where the 1951 & 1964 local directories list 16 St John’s Street as the Salvation Army Hall (sandwiched between two builders’ yards). In 1951 26 St John’s Street was the Salvation Army Officers’ Quarters.

Sources: James Gardner, ‘With God on their Side: William Booth, The Salvation Army and the Skeleton Army Riots’ (2022); British Newspaper Archive; local directories.

- Lewes Railway Photographs (by Anonymous)

These three photographs and the enclosed commentary reached me by post in June in an envelope addressed to ‘Dr John Kay, Local History Authority, Ringmer’. Well done, Royal Mail! The commentary explained that the sender had seen the recent article in The Lewesian, and included the note that the photographers Les Elsey and Jack Scrace were now deceased, but that the sender was sure that they would have no objection to the Lewes History Group publishing their photographs. The sender however omitted their name.

Are these three photographs of interest to the Lewes History Group?

The first photograph of a goods train entering Lewes station from the tunnel was taken about 1910. It shows London, Brighton & South Coast Railway 0-6-0 locomotive no.550 hauling a goods train, with the fireman poised to jump off the footplate as it entered the station.

Wikipedia adds that 550 was one of the LB&SCR C2 class locomotives, designed by their engineer Robert Billinton, but built under contract by the Vulcan Foundry in Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire, between 1893 and 1902. They were therefore known locally as ‘Vulcans’. Designed to pull freight trains, they proved reliable and could run at speed, so were often also used for secondary passenger services. They passed first to the Southern Railway and later to British Railways. More than half of them, including this engine, were later rebuilt with a larger boiler and smokebox, with that last survivors withdrawn only in February 1962. Many of them had pulled trains for well over a million miles each by the time they were withdrawn and scrapped. There are no survivors from this class.

No.550 (renumbered 2550 by Southern Railway and 32550 by British Rail) was one of the last ten built, and entered service in January 1902. It was rebuilt in the more powerful C2X format in 1910, one of the first dozen so modified. In October 1940 it was attacked by the Luftwaffe, and crashed into a German bomb crater, killing the driver. The fireman survived by jumping from the footplate into a ditch by the side of the line. The locomotive was repaired, and survived until December 1961.

Photograph from https://thesussexmotivepowerdepots.yolasite.com/horsham.php

The second and third photographs both feature the same British Rail 2-6-4 tank engine no.80154, the last locomotive ever built at the Brighton Locomotive Works, in 1957. One, taken by Les Elsey, shows it leaving Lewes and climbing Falmer Bank on 13 April 1958. This shows what the (wild) western end of Lewes looked like before the Barons Down housing estate smothered it.

The last photograph, taken by Jack Scrace in March 1958 on the final day of the East Grinstead to Lewes service, was taken from the coach behind locomotive 80154 as it entered Lewes station. This is on the line (finally closed in 1969) that passed across the Cliffe High Street bridge and then curved down behind the backs of the houses on Friars Walk into the station. The houses on the horizon are the backs of those on Mountfield Road. This area is now part of the Railway Land Nature Reserve and the Court Road housing estate.

Wikipedia adds the information that no.80154 was later moved from Brighton locomotive shed to Nine Elms in London. It was withdrawn from service in 1967, after a career of just ten years. The image below shows the staff of the Brighton Works posed with their final locomotive.

Image from mybrightonandhove.org.uk

- Lewes in the 1950s: how to qualify for a council house (by Chris Taylor)

Between 1945 and 1950, in response to the acute post-war shortage, Lewes Borough Council built 186 new houses and flats, and supplied 42 new temporary bungalows. A total of 310 families comprising 1081 people were found homes in these and older council properties in the immediate post-war years. The rate of house-building, council and private, remained rapid in the 1950s but, nationally and locally, demand continued to exceed supply. In February 1950 the waiting list in Lewes stood at 537 applications. Like their colleagues across the country, Lewes Borough councillors were obliged to devise a method for establishing which applicants should be given priority. The system they introduced in September 1950, driven as it was by the need to be seen to operate scrupulously fairly, was comprehensive and therefore complicated.

First, applications were placed in one of five categories:

Category A – families living in, or with a member working in, the borough who were sharing accommodation with another household

Category B – families living in, or with a member working in, the borough who were tenants of houses or self-contained flats

Category C – people not at present living or working in the borough (In practice, applicants in this category were regarded as of low priority and were almost never successful)

Category D – elderly couples and other two-person families living or working in the borough

Category E – single elderly people and other one-person families living or working in the borough.

In order to discriminate between applicants in Categories A and B, a points system was introduced, as follows:

| Basic Points | Bedroom deficiency | 10 points per bedroom |

| Shared accommodation | 15 to 25 points | |

| Degree of overcrowding | 5 points per person | |

| Broken families | 5 points | |

| Disability | 1 to 10 points, depending on severity | |

| Travelling to work | 1 to 5 points, depending on time taken | |

| Ill-health | Medical Officer of Health to award points | |

| Insanitary house | 5 to 20 points |

| Balancing points | War service | 1 point for each year |

| (in the case of a tie) | Civil defence service | 1 point for each year |

| Length of residence | 1 point for each year (max 20) | |

| Length of employment | 1 point for each year (max 20) | |

| Date of application | 1 point for each year on list | |

| Excessive rent | 1 to 5 points |

Councillors serving on the Selection of Housing Tenants sub-Committee met monthly throughout the 1950s to allocate council accommodation as it became available. Each time they considered a list prepared by council officers and chose:

(a) an equal number of top-pointed cases in categories A and B

(b) applicants in categories D and E, provided suitable accommodation was available for them

(c) other priority cases outside the classification scheme, such as

- people given notices to quit, supported by a court order

- people obliged to quit through slum clearance

- people living in property requisitioned by the council during the war, which had been re-possessed

- tuberculosis cases certified by the Medical Officer of Health

- special cases (such as, in December 1956, two Hungarian refugee families fleeing the consequences of the Warsaw Pact invasion, who were found council flats)

- exchanges and transfers between council properties.

In addition to all these calculations, whenever possible, one in eight dwellings were to be allocated to young married couples without children.

Navigating these complexities, the sub-committee doggedly discharged its brief throughout the decade. For example, at their June 1952 meeting, allocations to new houses in Hereward Way included the following:

- a 3-bedroom house allocated to a family of four, wife expecting, occupying two rooms and sharing facilities with seven other adults

- a 2-bedroom house allocated to a young married couple, wife expecting

- a 3-bedroom house allocated to a family of six with four children under four years, occupying a small cottage. On the Medical Officer’s recommendation, owing to a case of tuberculosis

- a 3-bedroom house allocated to a family of four, occupying one bedroom and sharing facilities in parents’ house with four other residents.

In September 1959 the council abolished the points system. The waiting list had been reduced to about 200 and its unwieldy nature had, in their view, made it outdated. In future each application was to be considered on its individual merits. The length of time the application had been on the waiting list was to be the main determinant, but other factors could be taken into account, such as:

- standard of current accommodation

- broken families

- war disability

- shared kitchen

- length of residence in Lewes

- other exceptional circumstances.

The one in eight ratio for young married couples was retained, but the council firmly rejected the suggestion that applications might be accepted from couples who were not yet married. In 1962 they relented to the extent of allowing engaged couples to apply, provided of course that proof of intended marriage could be provided.

Sources: Lewes Borough Council Housing Committee minutes ESRO DL/D/169/10-12

- Mick Jagger in Lewes Prison

On 28 June 1967 Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones drove to court in Chichester in a blue Bentley Continental. He was charged with possession of four amphetamine tablets after a police raid on Keith Richards’ Redlands Estate, West Wittering, Sussex. This was the event at which the police discovered Marianne Faithfull wrapped only in a fur rug, produced at the trial as evidence.

After being found guilty, Jagger was transferred to Lewes Prison in a police van, to await sentence two days later. He was then given a fine plus three months imprisonment. However, after a single night in Brixton he was released pending an appeal, which resulted in his sentence being reduced to a conditional discharge. He became, however, one of the many thousands of prisoners welcomed by Lewes prison over the years, including Eamon de Valera when imprisoned after the Easter Rising and the gangster Reggie Kray.

John Kay

Contact details for Friends of the Lewes History Group promoting local historical events:

Sussex Archaeological Society

Lewes Priory Trust

Lewes Archaeological Group

Friends of Lewes

Lewes History Group Facebook, Twitter