Please note: this Bulletin is being put on the website one month after publication. Alternatively you can receive the Bulletin by email as soon as it is published, by becoming a member of the Lewes History Group, and renewing your membership annually.

- Next Meeting: 9 October 2023, Guy Blythman, ‘Traditional Windmills’

- The Crisp Silver Challenge Cup (by Chris Taylor)

- The Westgate Ruins

- Lewes in 1775 (by Chris Grove)

- William Huntington, S.S.

- Contrasting Non-Conformist Philosophies

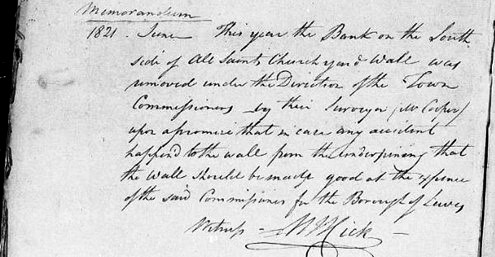

- A note in the All Saints parish register

- D’Aubigny Hatch, Lewes photographer

- Bull House open to visitors

- Beatrice Temple – council housing champion (by Chris Taylor)

- Next Meeting 7.30 p.m. King’s Church, Lewes Monday 9 October Guy Blythman Traditional Windmills in Sussex and Lewes

Windmills were a familiar, indeed iconic, feature of the Sussex landscape. Guy Blythman will be discussing their history and development with particular reference to those in the Lewes area.

He will give an overview of windmill history from their medieval origins to their decline in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He will analyse the various types of windmill and the different uses to which they were put. Finally he will look at the histories of some individual mills in Lewes and Kingston. As an expanding market town in the 18th and 19th centuries Lewes needed mills to feed its growing population. Traditional windmills today may seem an eccentricity, quaint survivors of a long-vanished age, but they produced the flour from which the bread our ancestors ate was made.

Members are requested to register in advance, so that we can monitor numbers attending. Non-members wishing to attend should register and pay in advance, as usual. From November we shall be returning to Zoom meetings for the winter season.

- The Crisp Silver Challenge Cup (by Chris Taylor)

In May 1939 the Lewes Borough Council inaugurated an annual garden competition for council tenants with the aim of enhancing “the beauty of the estates”. The Mayor, Lt. Colonel Charles Crisp, donated the prize for the best garden: the Crisp Silver Challenge Cup, to which was later added the Stacey Cup for the runner-up. The winner in the first two years was Mr W.H. Dumbrell of 5 Lee Road, Landport. The council revived the idea after the war in 1948, with a more ambitious scope. The two judges toured the gardens at each estate and awarded prizes in several classes: for professionals, for amateurs at each estate, for houses with ‘no menfolk’ and for gardens at prefabs. Once again, Mr Dumbrell triumphed overall. Winners of the Crisp Cup in subsequent years include Mr H. Shepherd of 22 Pellbrook Road, Landport (1949) and Mr A. Goldsmith of 9 Lee Road, Landport (1950 and 1951). The competition went ahead for the last time in 1953, with only 14 entrants, when Mr F. Jones of 58 North Way, Nevill won the cup.

Does any reader know what happened to the Crisp and Stacey cups thereafter? Information about their eventual destination and anything more in general about the garden competition would be most gratefully received. Please send me an email at membership@leweshistory.org.uk.

- The Westgate Ruins

James Lambert senior produced several pictures showing the ruins of the former Westgate, as seen from the High Street, the earliest of which is dated 1772. A decade earlier the walls of the former bastion had been removed, probably to widen the High Street. This shows the view looking into the southern bastion, so the building to the left is Bull House, with behind that Westgate Chapel. The chapel’s entrance gate was immediately next to the bastion.

Sources: The first picture is from John Farrant, ‘Sussex Depicted’, published in 2001 as Sussex Record Society volume 85. The lower picture showing the view a decade earlier is from a pre-1919 postcard by an anonymous publisher.

- Lewes in 1775 (by Chris Grove)

The description of Lewes below is taken from the 1775 edition of ‘The Complete Gazetteer of England and Wales’, snappily subtitled ‘An accurate description of all the Cities, Towns and Villages in the Kingdom, shewing their situations, manufactures, trades, markets, fairs, customs, privileges, principal buildings, charitable and other foundations, etc, etc, and their distances from London, etc, with a descriptive account of every county, their boundaries, extent, natural produce, etc, including the chief harbours, bays, rivers, canals, forests, mines, hills, vales and medicinal springs, with other curiosities of both nature and art, pointing out the military ways, camps, castles and other remains of Roman, Danish and Saxon antiquity’. The Gazetteer was printed for G. Robinson in Paternoster Row, London.

“Lewes, Sussex, 50 miles from London, is famous for a bloody battle near it, wherein King Henry III was defeated and taken prisoner by the Barons. It is so ancient, that we read the Saxon King Athelstan appointed two mint houses here, and that in the reign of Edward the Confessor, it had 127 burgesses.

Lewes is a pleasant town and one of the largest and most populous in the county. It stands in an open champaign country, on the edge of the South Downs. It is an ancient borough by prescription, by the style of constables and inhabitants. The constables are chosen yearly. It has sent burgesses to Parliament ever since the 26 th year of Edward I.

Lewes has six parishes, which have each their church. It has handsome streets and two fair suburbs. It carries on a good trade and the River Ouse runs through it, which brings goods in boats and barges from a port eight miles off. On this river there are several iron works where cannon are craft for merchant ships, besides other useful works of that kind.

A charity school was opened here in 1711, where 20 boys are taught, clothed, and maintained at the expense of a private gentleman by whom they are also furnished with books; and eight boys more are taught here at the expense of other gentlemen.

There are horse races almost every summer, for the Kings Plate of £100. The roads here are deep and dirty, but then it is the richest soil in this part of England. The market is on Saturday, and the fairs on 6 May, Whitsun – Tuesday, and 2 October.

From a windmill near this town, there is a prospect which is hardly to be matched in Europe for it takes in the sea for 30 miles west, and an uninterrupted view of Banstead Downs, which is full 40 miles. Between the town and the sea, there is the best winter game that can be, for a gun, and several gentlemen here keep packs of dogs; but the hills hereabouts are so deep that it is extremely dangerous to follow them, though their horses will naturally run down a precipice safely, with a bold and skilful rider.

On the east side of the town there has been a camp, and it had formerly a wall, of which few remains are now to be seen, with a castle long since demolished. [Presumably this refers to Mount Caburn]

The timber of this part of the county is prodigiously large. The trees are sometimes drawn to Maidstone and other places on the Medway, on a sort of carriage called a tug , drawn by 22 oxen a little way, and then left there for other tugs to carry on, so that a tree is sometimes two or three years drawing to Chatham; because, after the rain is once set in, it stirs no more that year, and sometimes a whole summer is not dry enough to make the roads passable.

It is cheap living here and the town, not being under the direction of a corporation, but governed by gentlemen, it is reckoned an excellent retreat for half pay officers who cannot confine themselves to the rules of a corporation.”

- William Huntington, S.S.

William Huntington (1745-1813), who described himself as ‘the coal heaver’ was born in Cranbrook, Kent, and died at Tunbridge Wells. He was his mother’s tenth child, but the only male to survive to adulthood. His true father is said to have been his nominal father’s employer, rather than his mother’s husband, a farm labourer. He was baptised under the name William Hunt at the age of five, but as a young man fathered a child himself, fleeing the county and changing his name to Huntington to escape his responsibilities. Later that same year he married a servant girl and moved to Mortlake in Surrey, and later to Sunbury on Thames. His work was generally unskilled or semi-skilled, driving hearses and coaches, gardening or carrying coal for Thames barges, and he spent some time as a tramp. He was frequently hungry as a child and a young man.

In 1773 he had a vision of Christ which convinced him that he was a member of God’s elect, those predestined to enter heaven. He associated with a variety of Calvinist groups, including Baptists and Methodists, and became known for his biblical knowledge and fiery evangelical preaching. He wrote at this time ‘When God sent me out I was friendless and defenceless; poor to an extreme, and illiterate to the last degree; without a Bible or book of any kind; and I laboured hard for bread … I was sent into dark corners where there was no light nor truth … He gave me great understanding in his word, which I never had before, so that I was astonished at myself.’ He established his own congregations at Thames Ditton and Woking in Surrey, and preached across a wide circuit of independent chapels in London, Surrey and Sussex. As his fame grew he established a large London chapel, where his hearers included members of the nobility and even the royal family, though he always preferred to preach to the poor. He wrote over 100 books, and was an enormously enthusiastic and influential correspondent.

As his influence expanded he became close to Rev Jenkin Jenkins, minister at the Old Chapel on Chapel Hill, and when Jenkins left that chapel to found his own chapel, Jireh, William Huntington supported him and was a regular preacher there. Huntington had added the letters S.S. [sinner saved] to his own name and W.A. (Welsh ambassador) to Jenkin Jenkins’.

Two oil portraits of William Huntington in the National Portrait Gallery. The portrait on the left was painted in 1803 by Domenico Pellegrini. An engraving based on this portrait was widely distributed following his death. The portrait on the right is by an anonymous artist.

William Huntington had 13 children by his first wife, but two years after her 1806 death he married again. By this time he had a farm in Hendon, his own carriage with his initials and ‘S.S.’ emblazoned on every panel, and annual income estimated at £2,000 p.a. – far above that that of his typical hearers. He saw this as the means ‘to show the Philistines what God has done for the coal heaver’. His second wife was Lady Elizabeth Sanderson, widow of Sir James Sanderson, a former Lord Mayor of London. She was twenty years his junior, and continued to use the name Lady Sanderson after their marriage. In 1810 his Providence Chapel in London bunt down, but by now he could command extensive resources, and spent £10,000 building a new, larger chapel in Gray’s Inn Road. When he died at Tunbridge Wells in 1813 his body was brought in a great procession to Lewes, where he was buried at Jireh beside Jenkin Jenkins, who had died in 1810 – perhaps the best attended funeral Lewes has ever seen, with hordes of participants travelling down from London for the event.

His 20th century biographer regarded him as the greatest preacher of his day, while Lady Sanderson’s view was that he was a teacher greater than any who had moved on earth since the days of St Paul. Huntington himself claimed that his teaching was often extemporary, inspired by the Holy Spirit. He claimed to be a prophet. However, he did not have a high regard for other contemporary Christians, inside or outside the established church. An extreme Calvinist, he had equally little time for Anglicans, Baptists and Wesleyans. He thought Methodism the work of the devil. Many of them cordially returned the feeling. The Countess of Huntingdon’s circle and the Anglican evangelicals such as Richard Cecil viewed him with dismay. William Huntington himself claimed that he had opposed none but imposters, hypocrites, heretics, devils and sin. He constantly identified anyone who opposed him in any way as an enemy of God.

The inscription on his panel of the tomb outside Jireh, which he composed himself shortly before his death, reads “Here lies the coalheaver who departed his life July 1st 1813 in the 69th year of his age, beloved of his God but abhorred of men. The omniscient Judge at the grand assize shall ratify and confirm this to the confusion of many thousands, for England and its metropolis will know that there has been a prophet amongst them.” A memoir, a farewell sermon and six volumes of his letters were published in the decade after his death.

The portrait on the left was at Jireh chapel. The caricature on the right, from the National Portrait Gallery, was an etching by a follower of Thomas Rowlandson, and published more than a decade after his death.

Sources: Wikipedia; https://www.christianstudylibrary.org/article/william-huntington#endnote-content-7. the National Portrait Gallery.

- Contrasting Non-Conformist Philosophies

John Wesley believed that his followers needed to hear different styles of preaching. Thus the Wesleyan church of the 19th century appointed ministers to its different stations for just a year at a time. Reappointment to the same station was possible, but after three years the minister invariably moved on. These men and their families led peripatetic lives. The consequence was that during the 19th century the Lewes Wesleyan Chapel on Station Street was led by more than thirty different ministers. Preparing a comprehensive list would be a challenge. Those ministers and their wives came from all over the country, and several had also served as missionaries abroad, so they brought with them a great diversity of experience of the Christian world (and doubtless some unfamiliar accents to Lewes ears). This regular rotation continued in the 20th century, though the maximum permitted stay at Methodist chapels was extended.

At the other extreme were Independent chapels like Jireh, founded in 1805 just two years before the Lewes Wesleyan church. At Jireh just four ministers, Jenkin Jenkins, John Vinall senior, his son John Vinall junior and Matthew Welland, covered the entire 19th century. Jireh only ever had seven ministers in its entire history of almost two centuries, though for several decades in the 20th century it managed without a professional leader.

- A note in the All Saints parish register

The note below was made on the front flyleaf of the All Saints parish register of baptisms. The town commissioners presumably wanted to remove the bank to widen Friars Walk, and the incumbent was concerned to record for posterity their promise to make good at their own expense any consequent problems affecting the wall’s stability.

- D’Aubigny Hatch, Lewes photographer

Offered for sale on ebay this summer by the same seller were two cartes de visite described on the elaborately printed reverse as produced by D’Aubigny Hatch, of the County Photographic Studio, 47-48 High Street, Lewes. He is rarely met with as a Lewes photographer, and according to the Sussex Photohistory website he was in business in Lewes for just a single year, 1878. This studio had been established by the more prolific photographer William Shelley Branch, who then moved his business to his mother’s fancy goods store at 16 High Street.

The birth of Henry Dobney Hatch was registered in the first quarter of 1840 at Oxford, where his parents Henry Hatch and Eliza Dobney had married in 1838. He grew up in High Street, Oxford, where in 1851 his father was a ‘boot and shoe factor’ with a staff of five, and later became a draper. In addition to his wife and large family in Oxford, his father had by 1861 established a second ‘wife’ and family in Kensington, to which by 1871 he transferred his business. By 1861 Henry D. Hatch had established himself in Magdelen Street, Oxford, at the age of 21, as a draper employing three male and four female staff. Later censuses show that he had two sons born in Oxford in the mid-1860s, but another born in Newbury (his wife’s birthplace) about 1868 and yet another at Ipswich about 1871.

In the mid-1870s he acquired an established photographic studio at 33 Western Road, Brighton, which he ran for about 5 years under the name D’Aubigny Hatch. The change from Dobney to D’Aubigny carries shades of Tess of the D’Urbervilles (published by Thomas Hardy in 1891), but the Dobney surname is indeed supposed to have originated from one of William the Conqueror’s comrades, who came from the Normandy village of Aubigny.

His stay in Lewes was indeed brief – in October 1878 the Newbury Weekly News reported the death of the wife of Henry D. Hatch of Tunbridge Wells and thereafter he advertised regularly in the Kent and Sussex Courier as Mr D’Aubigny Hatch, proprietor of a business selling stationery, fancy goods and toys in Oxford Terrace in that town. In the 1881 census he was living in Oxford Terrace, aged 41 and described as an importer of foreign goods and stationer, with four sons aged between 17 and 10, and a new young wife from Tunbridge Wells who was aged 24.

He remained in business in Tunbridge Wells until the late 1880s, and was noted giving popular lectures on American humour, including that of Mark Twain, and on dress, its history, curiosity and absurdity. In the 1888 both he and his wife contributed to the newly established hospital, his present being a large parcel of books. In the 1891 census he, his wife and two daughters of his second marriage lived in Islington, where he was described as a commercial traveller, and by 1911 they were living in Hampstead, now once again Henry Dobney Hatch, where he gave his occupation at the age of 71 as a stationer and bookseller. His death at the age of 83 was registered in Hertfordshire in 1924.

Sources: Sussex Photohistory and Familysearch websites; British Newspaper Archive; www.wikitree.com (Hatch & Dobney family).

- Bull House open to visitors

The Sussex Archaeological Society have long owned Bull House, the 15th century timber-framed house on Lewes High Street best known as the home of Tom Paine. This was once an inn, just inside the town’s West Gate, but has served many different purposes over the centuries. In recent years it has been the Society’s administrative centre, but it has now opened its doors to visitors.

The Sussex Archaeological Society have long owned Bull House, the 15th century timber-framed house on Lewes High Street best known as the home of Tom Paine. This was once an inn, just inside the town’s West Gate, but has served many different purposes over the centuries. In recent years it has been the Society’s administrative centre, but it has now opened its doors to visitors.

Photograph: Sussex Past

Bull House is now open to the public between 11 am and 3 pm from Friday to Sunday. The admission charges is £5 (£3 for senior citizens and children, and free for children or Society members). Alternatively there will be guided tours on Thursdays at 11 am and 1.30 pm, led by the curator Emma O’Connor. These tours must be pre-booked, and there is a charge of £20.

- Beatrice Temple – council housing champion (by Chris Taylor)

Beatrice Temple served on Lewes Borough Council’s housing committee in the 1960s. During these years the Landport, Winterbourne and Church Lane estates were extended, the De Montfort and St Pancras developments were completed and negotiations got under way for what was to become the Malling estate. The committee was thus responsible for a considerable expansion of the council’s housing stock, for its subsequent maintenance and for the allocation of an increasing number of tenancies. In all this Miss Temple was a constant and often guiding presence.

Beatrice was born in 1907 in India, where her father, Colonel Frederick Temple, was serving with the Indian Army. After boarding schools in the home counties, she looked after an elderly uncle in the south of France and travelled widely in Europe. She was in Austria at the time of its anschluss with Germany and witnessed from her upstairs window in a small town a parade in which Adolf Hitler accepted the applause of the townsfolk.

In 1939 she volunteered for the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) – the predecessor of the Women’s Royal Army Corps (WRAC), which had been formed to free up men for front line duties. She was appointed to the rank of captain and, after a year in which she demonstrated the required abilities, was promoted to take national command of the Special Duties Section. Their role was to form, in the event of a German invasion, a network of radio operators at secret control stations across the country and to spy on the broadcast activities of enemy agents. They soon acquired the nickname, ‘Secret Sweeties’. Beatrice interviewed potential recruits at Harrods Tea Rooms (where else?) and spent most of the war in a constant round of country-wide inspections of control stations, checking on the efficiency of the operation and the welfare of her staff. She kept a limpet mine as a souvenir.

Captain Beatrice Temple 1940 Mayor Beatrice Temple in 1972

Beatrice was a niece of William Temple, archbishop of Canterbury from 1942-1944. Renowned as a leading advocate within the Church of engagement with contemporary social and economic issues, Archbishop Temple exerted a huge influence on the Beveridge Report, which set out the essential architecture of the post-war welfare state reforms. Beatrice demonstrated a similar outlook. After the war she worked in London as a hospital records officer and then for the National Corporation for the Care of Old People, a part of the Nuffield Foundation. Having moved to Sussex in the mid-1950s, she became heavily involved in the civic life of the area, a manager of Wallands Primary School and a governor of Lewes County Secondary. She became honorary secretary of the Sussex Housing Association for the elderly and chairman (sic) of the Gundreda Housing Association in Lewes, responsible for converting Fairholme in Southover High Street, and later Clevedown in Brighton Road, to homes for elderly tenants.

Her parents had retired to a house in Keere Street and Beatrice lived there until her mother’s death in the mid-1960s, when she moved to St Anne’s Crescent. Her father had been elected a Conservative councillor for Priory ward in 1954. In 1960, after his death, Beatrice was elected unopposed as a Conservative in the same district and took his place on the council and on the housing committee, of which she took the chair in June 1968. Her appointment, however, coincided with her fellow Conservative councillors’ decision to approve in principle the sale of council houses, a concept to which Beatrice was fundamentally opposed. After a long debate, the full council adopted the policy on 31 July 1968 by 13 votes to 10. Beatrice abstained: “I am in a very awkward position. My opinions have been known for many years and I can’t change them. After this meeting I shall take the necessary steps …” She resigned from the housing committee, an event ‘noted with regret’ at its next meeting.

Beatrice remained on the borough council and its successor, Lewes District Council, until her retirement in 1976. She topped the poll in the 1973 district council election with nearly 60% of the vote. She also served as county councillor for Castle and Bridge wards from 1967-1973. She became an alderman and Mayor of Lewes in 1972-73, the second woman to hold the office (after Anne Dumbrell). When she died in 1982, many tributes were paid to a much loved and respected ‘gentle and ladylike’ local figure with ‘a natural friendliness and a pretty wit’.

Temple family home in Keere Street

Question: I have been unable to discover whether Temple House, the former cinema site in the High Street (currently Seasalt and adjoining offices), was named in her honour. Does anyone know?

Sources: Lewes Borough Council Housing Committee minutes ESRO DL/D/174; Sussex Express 1968 and 1982; British Resistance Archive https://www.staybehinds.com/beatrice-temple; Lewes News, September 1980; Graham Mayhew: ‘Lewes Mayors 1881-1981’; and correspondence;

100 Lewes Women: the first three women mayors:https://vote100lewes.wordpress.com/2019/05/17/100-lewes-women-26-28-the-first-three-women-mayors/

John Kay

Contact details for Friends of the Lewes History Group promoting local historical events:

Sussex Archaeological Society

Lewes Priory Trust

Lewes Archaeological Group

Friends of Lewes

Lewes History Group Facebook, Twitter