Please note: this Bulletin is being put on the website one month after publication. Alternatively you can receive the Bulletin by email as soon as it is published, by becoming a member of the Lewes History Group, and renewing your membership annually

1. No August meeting

2. Christmas 2024 meeting

3. Heritage Open Days, 13-15 September 2024

4. The First Lady of Lewes Priory

5. Baxter’s Illustrated Guide to Lewes

6. John Shelley’s copy of Benjamin Franklin’s Essays

7. The King’s Arms, North Street

8. Charles Dawson of Castle Lodge

9. The Phoenix Workman’s Institute

10. Lewes Arms prints (by Mathew Homewood)

1. No August meeting

As usual, we have not planned a meeting for August. Our next Monday evening meeting will be on Monday 9 September.

2. Christmas 2024 meeting

We are planning a rather different format for our Christmas meeting this year, on Monday 9 December. Instead of a single long talk, we shall have a series of short presentations in which members will introduce us to specific Lewes heirlooms that have come into their possession. We already have three volunteers, who will be telling us about a timepiece made in Lewes, a bottle made for a Lewes wine merchant and an 18th century book printed and published in the town. We are seeking two or three further presentations of a similar nature – no more than 10 minutes per item. Please contact johnkay56@gmail.com.

Our Christmas meeting this year will, although in our winter Zoom period, be a live meeting at which we shall be offering mince pies and mulled wine to those members who arrive in time.

3. Heritage Open Days, 13-15 September 2024

This year’s Heritage Open Day weekend, run by the Friends of Lewes, will be from Friday 13 to Sunday 15 September. There will be free access to fourteen different buildings, some with special tours, and five different guided walks.

Lewes History Group will once again be taking part. You can find us throughout the Saturday and Sunday at Lewes House on School Hill. We will have on display an exhibition of members’ recent research and a selection of our publications for sale.

The event is preceded by a talk from Marcus Taylor at 7.30 p.m. on Tuesday 20 August 2024 in Eastgate Church Hall in which he will preview some of this year’s highlights. Places for the talk are available both live and on Zoom – free to members of the Friends of Lewes but available to others at a cost of £4 if you book through TicketSource. For details see www.friends-of-lewes.org.uk.

4. The First Lady of Lewes Priory

Bulletins no.128 & 163 recorded that when Lewes Priory was dissolved in 1538 its prior and monks were despatched to other duties or pensioned off, and the Priory itself was acquired by Thomas Cromwell. He promptly ordered the destruction of the Priory itself and the creation of a new mansion suitable for the residence of his newly-married only son Gregory. There is some uncertainty about Gregory’s date of birth – the online History of Parliament reports he was born before 1516, but Wikipedia thinks not until about 1520. The former seems more likely, as he was studying at Cambridge in the late 1520s.

Cromwell’s initial 1536 plans to establish a dynasty for his son had envisaged a Norfolk base, but the strong influence of the Duke of Norfolk in that county persuaded him to look elsewhere, and by late 1537 he had acquired Lewes Priory as an alternative. He wasted no time, with the huge Priory church demolished within weeks. Gregory & Elizabeth Cromwell and their baby son Henry arrived to take up residence in March 1538, and in her letter from that time included in Bulletin no.163 Gregory’s wife Elizabeth declared herself well pleased with their new home. Gregory Cromwell became a Sussex JP, alongside his father’s courtier-colleague Sir John Gage.

The Cromwells were not to remain in Lewes long. In 1539 Thomas Cromwell succeeded to the vacant post of constable of Leeds Castle, the previous constable having been executed and forfeited his post. Gregory & Elizabeth and their family were installed there in March 1539, after just a year in Lewes, and the Lewes premises were leased. His father forced Gregory, still a very young man, on Kent as one of the county’s two MPs, which displeased the Kent elite. He was not to remain long in Kent either.

Thomas Cromwell’s plans for his own retirement were based on his seat at Launde Abbey in Leicestershire, another monastic property that he had acquired. Those plans were of course dashed when in the summer of 1540, after the Anne of Cleves debacle, Cromwell himself fell foul of the tyrant he served and was executed. His properties were seized, and the Lewes estate became part of Anne of Cleves’ generous divorce settlement. Launde Abbey was eventually restored to Gregory & Elizabeth by King Henry VIII, with Gregory becoming the 1st Lord Cromwell. He attended the House of Lords in the 1540s, without making any great mark. He lived at Launde Abbey until his death in 1551 aged just over 30, and he is buried there in an elaborate tomb. He is believed to have died of the ‘Great Sweat’, which was rampant in that year.

Who was Elizabeth Cromwell, Gregory’s wife who had declared herself satisfied with her Lewes home? She is thought to have been born about 1518, one of ten children of the soldier and courtier Sir John Seymour. Her elder sister Jane (c.1509-1537) was a maid of honour to Queen Catherine of Aragon, and later the third wife of King Henry VIII, who died shortly after giving him the son that he craved, the future Edward VI. Thus at the time of Elizabeth’s marriage to Gregory Cromwell she was Henry VIII’s sister-in-law (for the few months until her sister’s death), and aunt to Edward VI.

Two of Elizabeth’s brothers also became courtiers who played prominent roles in England’s Tudor history. Edward Seymour (c.1500-1552) rose rapidly through the peerage to become the 1st Duke of Somerset. After the death of Henry VIII he became Lord Protector to the young Edward VI, his nephew. He was however forced out in 1549 and finally executed by his rival Northumberland in 1552. His younger brother Thomas Seymour (c.1508-1549) married Henry VIII’s widow Catherine Parr, who the king had left as one of the wealthiest women in England. He also famously dallied with the teenage Princess Elizabeth, who resided in their household. His numerous political intrigues, mainly against his brother, led to his execution in 1549.

If Elizabeth Seymour was indeed born about 1518, she cannot have been more than about 12 when she first married. Her first husband was the soldier Sir Anthony Ughtred (c.1478-1534), who was forty years her senior, and at the time Governor of Jersey. This seems unlikely to have been a love match, but she bore him two children, a son Henry born in Jersey in 1533-4 and a daughter Margery born about 1535 after her first husband’s death in Jersey, and after Elizabeth had returned to England.

Thus when Lady Elizabeth Ughtred married Gregory Cromwell in August 1537 she was probably still a teenager, though a widow with two young children. He was, in marked contrast to her first husband, close to her own age. They had been married only three months when her sister the queen died, and it was soon after this that they came to live briefly in Lewes. They had five children between March 1538 and 1545, three sons and two daughters. Her eldest son from this marriage was, like the eldest son of her first marriage, called Henry.

Thomas Cromwell’s sudden downfall in 1540 reduced at a stroke his dependents such as Gregory and his family from extreme wealth and influence to poverty. In one of Cromwell’s final letters to the king, beside pleading his innocence, he writes “I most humbly beseech your most gracious Majesty to be a good and gracious lord to my poor son, the good and virtuous lady his wife, and their poor children”. Elizabeth Cromwell herself, doubtless advised by her elder brother Edward, also wrote directly to her brother-in-law:

“After the bounden duty of my most humble submission unto your excellent majesty, whereas it hath pleased the same, of your mere mercy and infinite goodness, notwithstanding the heinous trespasses and most grievous offences of my father-in-law, yet so graciously to extend your benign pity towards my poor husband and me, as the extreme indigence and poverty wherewith my said father-in-law’s most detestable offences hath oppressed us, is thereby right much holpen and relieved, like as I have of long time been right desirous presently as well to render most humble thanks, as also to desire continuance of the same your highness’ most benign goodness. So, considering your grace’s most high and weighty affairs at this present, fear of molesting or being troublesome unto your highness hath disuaded me as yet otherwise to sue unto your grace than alonely by these my most humble letters, until your grace’s said affairs shall be partly overpast. Most humbly beseeching your majesty in the mean season mercifully to accept this my most obedient suit, and to extend your accustomed pity and gracious goodness towards my said poor husband and me, who never hath, nor, God willing, never shall offend your majesty, but continually pray for the prosperous estate of the same long time to remain and continue”

As noted above, these pleas were successful, and Launde Abbey and a title were restored to them.

Elizabeth’s two courtier brothers were executed in 1549 and 1552, and although she had a surviving brother and sister, they do not seem to have moved in court circles. In between, in 1551, her second husband Gregory Cromwell, the 1st Lord Cromwell, also died. The period of Seymour and Cromwell influence had passed – Gregory’s eldest son became a country gentleman.

Three years after Gregory Cromwell’s death, Elizabeth married again. Her third husband was Sir John Paulet (c.1510-1576), who as eldest son to the 1st Marquess of Winchester held the courtesy title of Earl of Wiltshire. He was a widower a few years her senior, with six children by his first wife. He had no more by his new Countess, probably in her thirties when she married him. She lived with him until her death in 1568, after which he married yet again, within six months of her death, to a very well-connected third wife. Her last father-in-law was a courtier with views flexible enough to hold very senior positions in the courts of Henry VIII, Edward VI, the Catholic Mary and her Protestant sister Elizabeth. After Elizabeth’s death her husband became the 2nd Marquess of Winchester, but it was his third wife who became the Marchioness.

Blended families were common in the 16th century, due mainly to the many premature deaths, and Lady Elizabeth’s seems to have been a success. Her eldest son Sir Henry Ughtred married Elizabeth Paulet, a daughter of her third husband, and her second son Henry, 2nd Lord Cromwell, married Mary Paulet, another of his daughters. Elizabeth & Mary Paulet were thus both promoted from being her step-daughters to become her daughters-in-law.

Sources: talk by Prof Diarmaid MacCullogh, ‘Thomas Cromwell, a Life’; Wikipedia; https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1509-1558/member/cromwell-gregory-1516-51

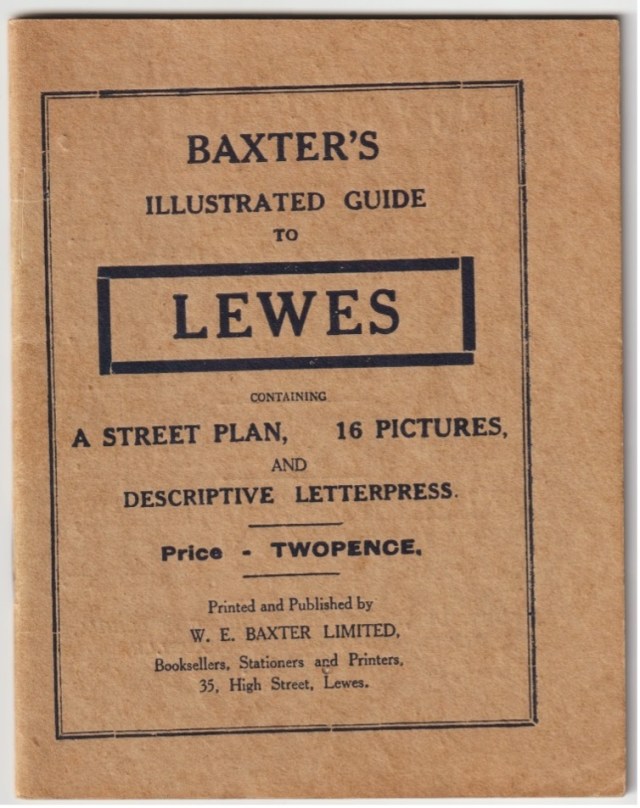

5. Baxter’s Illustrated Guide to Lewes

A recent addition to my collection is a copy of a pocket-sized booklet called ‘Baxter’s Illustrated Guide to Lewes’. Cheaply-produced, and originally sold for 2d, it includes 16 standard views of the town, focusing naturally on the main attractions. The total length is 40 pages, including advertisements. It was presumably intended as a keepsake for tourists.

Like many guidebooks it does not carry a date – no one wants to buy last year’s guidebook. So how old is it? Google quickly establishes that this guide went through many editions, some as late as the 1950s, though most of those shown have a landscape format to better-illustrate the pictures. None of the street-scenes include any motor vehicles though there is some horse-drawn traffic – but then the illustrations could be considerably older than the booklet itself.

The booklet’s text provides a few clues. The population of Lewes is stated to be 10,972. Mr Charles Dawson of Castle Lodge is mentioned as having discovered the famous Piltdown Skull “quite recently”. Most of the text outlines the town’s ancient history, with the latest date mentioned being the establishment of the Lewes Victoria Hospital in 1909.

The nine pages of advertisements offer the best guide to dating, as they at least are contemporary. J.C.H. Martin Ltd, motor engineers, Cliffe Bridge, advertise on the back cover. A few advertise telephone numbers – 45 for Martin’s; 67 for Browne & Crosskey, drapers; 81 for Baxter’s the publishers; 82 for Powell & Co, estate agents; and 94 for the White Hart. Others do not.

Census records show that 10,972 was the Lewes population in 1911 – by 1921 it had fallen to 10,797. The solicitor Charles Dawson claimed to have discovered the skull of Piltdown Man in 1912. One of the advertisers is Harris & Kenward (W.E. Clark), jewellers & silversmiths, Cliffe Bridge, and that firm’s website records that Wilfred Ernest Clark came to Lewes to take over that business in 1919. The other businesses advertising all ran from before the Great War until at least 1927. It thus seems likely that this particular edition was published c.1920 – after W.E. Clark arrived in 1919 but before the results of the 1921 census became available.

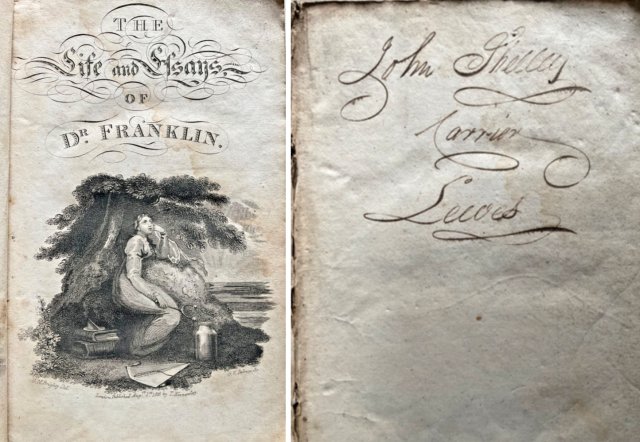

6. John Shelley’s copy of Benjamin Franklin’s Essays

Offered recently on ebay was a copy of Benjamin Franklin’s ‘Life and Essays’ published in London by T. Kinnersley in June 1816. The volume included a substantial biography of the famous American polymath, much of it autobiographical, plus extracts from his will and then more than thirty of his works on topics ranging from ‘The way to wealth’ and ‘Advice to a young tradesman’ via ‘The morals of chess’, ‘On early marriages’ and ‘Dialogue between Franklin and the gout’ to ‘Description of a new musical instrument’ and ‘The best method of guarding against lightening’. The flyleaf of the volume shows that it initially belonged to John Shelley, a Lewes carrier.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) was a remarkable man. Initially a printer, newspaper publisher and postmaster in Philadelphia, he became wealthy and famous as a writer, inventor, scientist, economist, educator, diplomat and political philosopher. He identified and named the Gulf Stream, and was an early researcher into electricity. At one time a slave owner, he became an active abolitionist a century before this cause eventually triumphed in America. He spent twenty years in London up to the declaration of independence as a representative of the American colonies, was a key figure in the American Revolution, and became one of the group of five men who drafted the American constitution. As the American ambassador to France from 1776 to 1785 he oversaw the close association between the two nations. His political views were regarded as radical.

John Shelley appears in John Viney Button’s 1805 directory as a carrier based in Lewes High Street whose waggons went to London and back three times per week – he had an effective monopoly in this trade for that route. From 1783 he was based at the White Horse Inn, 166 High Street, one of three houses pulled down in 1812 to make way for Castle Place. There seem to have been two John Shelleys engaged in this trade, father and son. The business survived the demolition of the White Horse, moving into the Castle Precincts at Brack Mount House. Bulletin no.134 reported that John Shelley retired from the business in favour of Joseph Shelley in 1824.

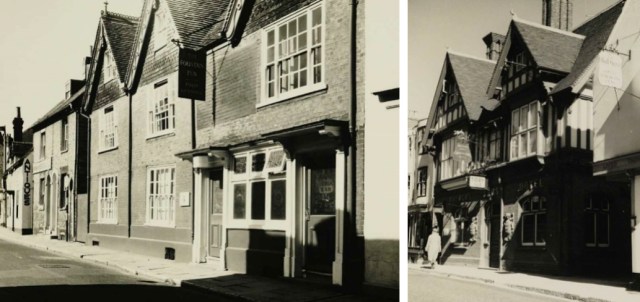

7. The King’s Arms, North Street

This image of the King’s Arms at 47 North Street (on the corner of Wellington Street) was taken by the Charrington Brewery, to which it once belonged, as part of an architectural survey of the brewery’s pubs. The photograph is now part of the National Brewery Heritage Trust collection, which is accessible online. This public house was demolished well within living memory, after a period of dereliction. The photographs in the archive are not dated.

Sources: https://www.historypin.org/en/a-history-of-pubs/; Wikipedia; LHG Bulletins nos.64, 129 & 144.

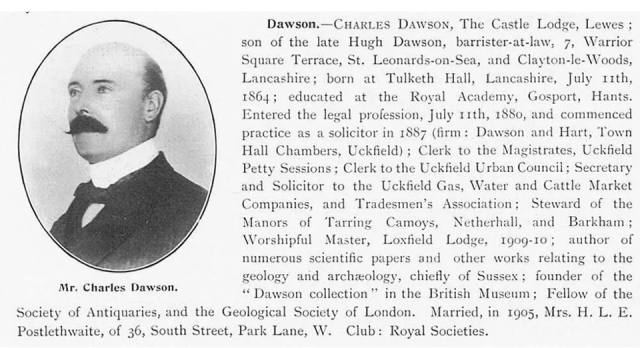

8. Charles Dawson of Castle Lodge

William Thomas Pike’s ‘Sussex in the Twentieth Century’, published in 1910, contains the photographs and brief biographies of the Sussex gentry and professional classes at that date – starting with those of the Dukes of Devonshire and Richmond. A number of their mansions are also shown. Smartly bound, it was sold to its subscribers, who were also those featured, so copies were included in many of the private libraries of the day. Copies of this book, many in excellent condition, appear regularly at local auctions. W.T. Pike of Brighton was also the publisher of the many ‘Blue Book’ local directories of the period, including that for Lewes, Seaford and Newhaven

A typical entry, reproduced below, is that for the Uckfield solicitor Charles Dawson (1864-1916), who lived in Lewes at Castle Lodge. Long an enthusiastic amateur archaeologist, in 1912 he was to be the discoverer of ‘Piltdown Man’, later revealed as a hoax for which he became, posthumously, the prime suspect. Subsequent investigation of his collections and his publications have revealed that they included many examples of fakes or planted evidence, leading the academic Miles Russell to conclude from his detailed studies that the whole of Dawson’s academic career was “built upon deceit, sleight of hand, fraud and deception” with his motive being to gain academic recognition.

Charles Dawson was certainly less than popular with contemporary members of the Sussex Archaeological Society, some of whom resented the manner of his acquisition of Castle Lodge, and his displacement of the Society as its tenants. His reputation has been scrutinised in considerable detail, and perhaps with more balance, in a long article by John Farrant published in Sussex Archaeological Collections volume 151, pages 145-180 (2013).

9. The Phoenix Workman’s Institute

This institution was built and furnished in 1896 by the proprietor of the Phoenix Ironworks, for the use of employees. In addition to a large hall, there were two bath rooms and a servery for the sale of refreshments. In connection with the institute there were cricket, football and quoits teams, with the recreation ground being situated in the Paddock. Three generations of the Unitarian Every family, leading members of Westgate Chapel, ran the Phoenix Ironworks. They were, by Victorian standards, enlightened and liberal employers.

Sources: Pike’s Blue Book for Lewes, Seaford & Newhaven for 1900-1: LHG Bulletins nos.112 & 155.

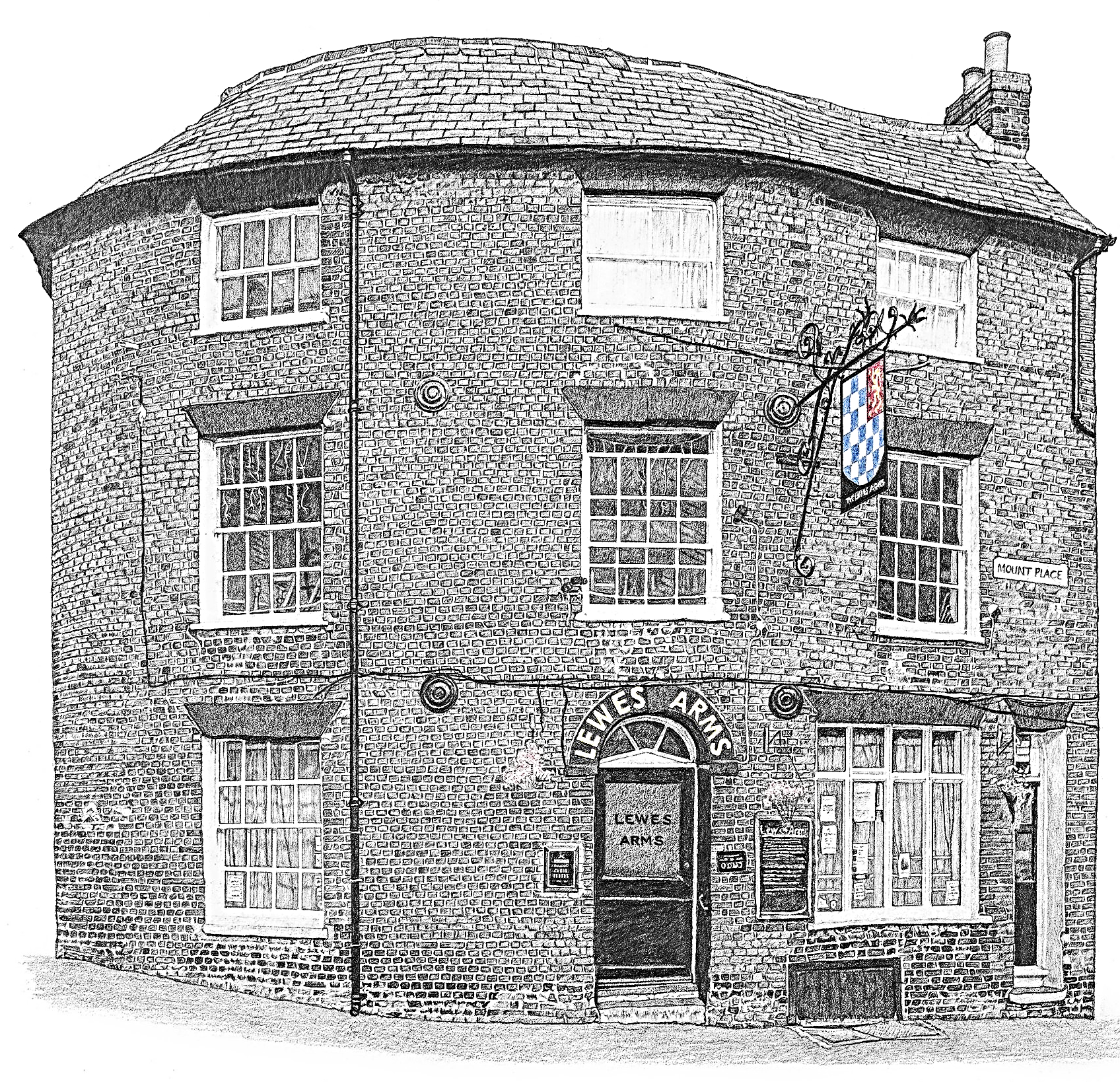

10. Lewes Arms prints (by Mathew Homewood)

This is a pencil drawing of the Lewes Arms that I created back in 2018. It is meticulously detailed, with almost every brick matching that of the building itself. I have now created a limited edition of 50 copies printed on high-quality thick ivory-coloured paper. The overall print is 28 x 28 cm, with the pub itself about 17 cm squared.

Most copies have already been sold, and one can be found on the wall of the front bar in the Lewes Arms itself. Copies are still available, unframed, at £45.00 each, signed and numbered. Please contact me via 01273 479467 or 07906 586726 for details.

John Kay 01273 813388 johnkay56@gmail.com

Contact details for Friends of the Lewes History Group promoting local historical events

Sussex Archaeological Society: http://sussexpast.co.uk/events

Lewes Priory Trust: http://www.lewespriory.org.uk/news-listing

Lewes Archaeological group: http://lewesarchaeology.org.uk and go to ‘Lectures’

Friends of Lewes: http://friends-of-lewes.org.uk/diary/

Lewes Priory School Memorial Chapel Trust: https://www.lewesprioryschoolmemorialchapeltrust.org/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LewesHistoryGroup

Twitter: https://twitter.com/LewesHistory