Please note: this Bulletin is being put on the website one month after publication. Alternatively you can receive the Bulletin by email as soon as it is published, by becoming a member of the Lewes History Group, and renewing your membership annually

1. Next Meeting: 12 January 2026: Chris Hare, ‘Richard Jefferies: a man out of time’

2. A.G.M. Report

3. A great fall of Chalk

4. Steere’s Charity

5. A well-travelled postcard of Southover Church

6. Ouse abuse (by Chris Taylor)

7. Merging the Lewes and Chailey Poor Law Unions

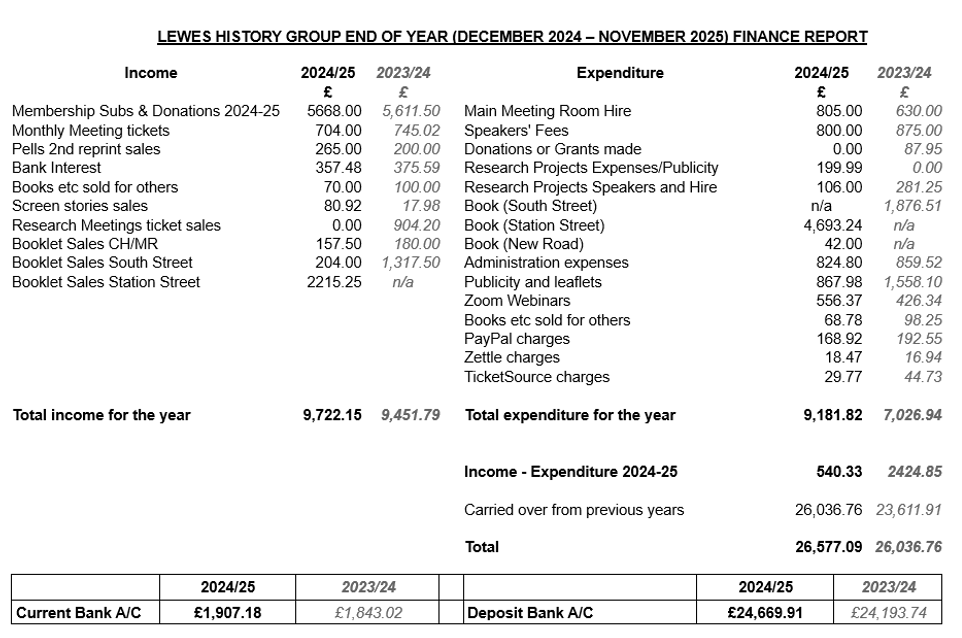

8. Treasurer’s Final Report for 2024/5 (by Phil Green)

1. Next Meeting 7.30 p.m. Zoom Meeting Monday 12 January

Chris Hare Richard Jefferies: a man out of time

Historian Chris Hare will be speaking about the life and work of the naturalist and novelist Richard Jefferies, a remarkable man who spent his final years living in Sussex, documenting the life of the county, and especially life on the Sussex Dowland, in the 1880s.

Members can register without charge to receive a Zoom access link for the event.

Non-members can attend via Ticketsource.co.uk/lhg (price £4.00).

In our recent survey over 70% of members supported continuing with zoom meetings in the winter months.

2. A.G.M. Report

- The Annual Reports published in Bulletin no.185 were approved.

- Appointment of officers. The following officers were appointed:

(a) Chair: Ian McClelland (also ‘Street Stories’ lead)

(b) Treasurer: Phil Green

(c) Secretary: Krystyna Weinstein

(d) Executive committee: Ann Holmes (Chair for EC meetings), John Kay (Bulletin editor), Bill Kocher & Paul Yates (Website managers) & Chris Taylor (Membership) - Membership subscription. It was agreed that the annual subscription should remain at £10 p.a. per member, and that admission to evening meetings should be free for members. Admissions charges for non-members should remain at £4 per meeting.

- There were no AOB items.

3. A great fall of Chalk About eight o’clock on Saturday night early in 1805 several persons in Lewes were alarmed by a strange rattling noise in the air, which they were totally unable to account for until the following morning, when it appeared that the noise was occasioned by an immense fall of chalk, in the pit belonging to Mr Hillman in South Street, Cliffe. It is extraordinary that the noise was scarcely noticed by persons living in the neighbourhood of the pit, although the fall is estimated at six thousand tons weight. It was productive of no damage whatever, as it fortunately happened at a time when the men had all left their work.

Source: 14 January 1805 Hampshire Chronicle

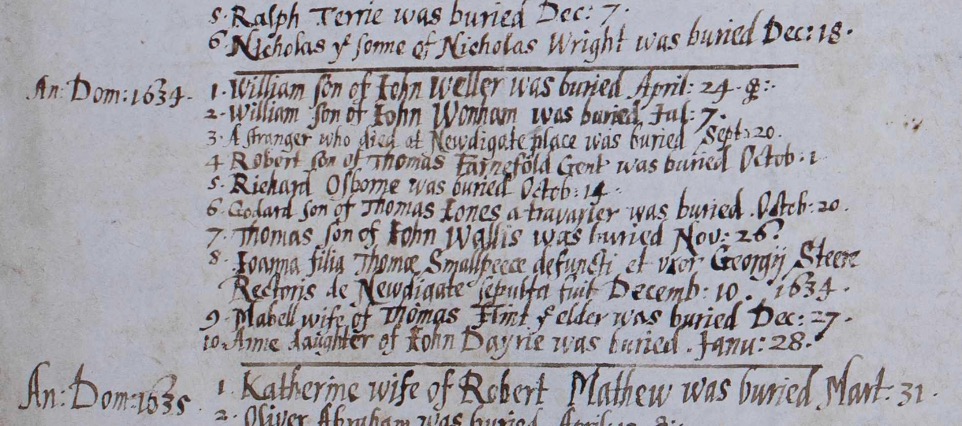

4. Steere’s Charity

Inserted into the Lewes Town Book, between the records of the law days held in the autumn of 1661 and 1662, is a page recording the establishment of Steere’s Charity under the 1 November 1661 will of George Steere of Newdigate in Surrey, clerk. His will had been made when he was in indifferent health, but he added a codicil on 3 June 1662, a week before his death. He was buried at Newdigate three days later. By his will he left the houses that he owned in Lewes, occupied by “one Legate, Peter Ray, Widow Braines and Widow Mote”, to the inhabitants of the town of Lewes. They were to pay an annuity of £4 p.a. to Rev George Steere’s widow Sarah and another annuity of £2 p.a. to Thomas Holmewood, the son of his “loving kinsman” Edward Holmewood of Lewes, but the residue of the income (and the entire income after their deaths) was left to support the maintenance of “one fitt person the sonne of godly poor parents in or neare to the sayd Towne of Lewes” for four years while they attended the Universities of Oxford or Cambridge. The income was then to be paid to one candidate after another, each for a four year period. He expressed a preference for the recipient to be “a sonne of a godly poore minister who hath truly laboured & endeavoured to wynne soules unto Jesus Christ”.

Steere’s Exhibition continued to enable young men from Lewes and its neighbourhood to attend Oxford and Cambridge colleges for more than two hundred years, until after the establishment of the Borough in 1881 it was combined with other town charities that also had educational aims. One of the houses that provided this income was Castle Hill House, 76 High Street, featured in Bulletin no.183, which George Steere had owned since at least 1624, and with which Edward Holmwood, draper, was also associated. The other three houses were nearby on the west side of St Martin’s Lane, very probably built on what had been the garden of this same property. Such charities, often established by clergymen who had themselves benefitted from a charity-sponsored education, were not uncommon in the colleges of the older universities – many years ago I was myself a beneficiary. However, this one raises some intriguing questions, most notably why the long-serving rector of a Surrey parish should establish a charity whose beneficiaries were to be the young men of the Lewes area.

As is often the case for people born in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the biographical information available about George Steere is incomplete. Venn’s ‘Alumni Cantabrigiensis’ is unusually tentative. It records that he was admitted as a sizar to Queen’s College at Easter 1600, but perhaps previously to Trinity College in June 1599, and that he came from Suffolk, probably from the parish of Bures St Mary. Sizar’s received financial help from their college in return for performing some menial duties, so we can conclude that he was probably born in the early 1580s and that he was more likely an academically-able young man from a modest social background than a scion of a wealthy family. He graduated with a BA degree about 1602-3 and was awarded his MA at a date after 1606. Venn also notes that he married twice (but gives an incorrect date for the death of his first wife) and that he was rector of Newdigate from 1610-1656 (the second date also apparently incorrect). He notes that there are two secondary biographical sources available, one published in the Surrey Archaeological Collections, but questions their accuracy.

Steere’s entry in the online Clergy of the Church of England Database also lacks information about his university career and his ordination, but does provide some information about his career between his graduation and his gaining his rectory. It records that on 23 October 1604 George Steere BA was licensed as both curate and schoolmaster at Chailey, with permission to serve as a schoolmaster anywhere in the Archdeaconry of Lewes. A second record dated 2 January 1607 marks his being appointed as sequestrator of Southover church, which was at that time served by a curate. The exact nature of his duties is not entirely clear, but it seems that he was at this time resident in the Lewes area. Then on 20 March 1610/1, now qualified by an MA, he was instituted as Rector of Newdigate in Surrey, a crown rectory.

He promptly took up his duties in Newdigate, and resided in that parish for more than half a century until his death in 1662. The parish registers are consistently completed in his distinctive hand from 1611 until 1660. The first section of his 1661 will, which was also written in his own hand, proclaims clear Puritan views:

“First and before all other things I comitt my soule into the hands of Almighty God my creator steadfastly trusting in the exceeding abundance of the uses of his free grace and tender murcie to bee saved through the alsufficient merritts of the active and passive obedience of my most blessed Lord and only saviour Jesus Christ”.

He remained in post undisturbed throughout the Civil War and the period of Cromwell’s rule. It isn’t clear why he ceased to fulfil his role in person for the last two years of his life. Did he, in his late seventies, simply require assistance or was he was displaced at the Restoration? After 1611 he is always described as of Newdigate, and he appears as a witness to the wills of several of his parishioners there, including nuncupative wills declared by a testator on his deathbed and written down later by the witnesses. His own will shows him as living in his own house in the parish.

Just a few weeks after his arrival in Newdigate he married Joan Smallpeece, the daughter of a yeoman farmer with a substantial estate in that parish and other surrounding parishes. The marriage took place at St Saviour’s church, Southwark, but George Steere recorded the event in his own parish registers too. The Victoria County History of Surrey notes that in 1614 he repaired and ceiled the chancel of Newdigate church at his own expense, and that in 1627 he contributed to two new windows there. This and the acquisition of his Lewes property suggests that he was now a man of some means, perhaps from his clerical income or perhaps from a dowry brought into the marriage by his wife. His will shows that by his death he owned property in Newdigate and Dorking as well as in Lewes. His wife’s father died in 1626 and her mother in 1632. Both their will’s mention their married daughters Joan Steere and her married sister Catherine Constable, but leave them only modest bequests. The great majority of the Smallpeece estate went to their eldest brother, the new head of the family. Her mother named Joan and her sister, rather than any of the menfolk of the family, as her executor. Joan the wife of George Steere, parson of Newdigate, was also the executor and residuary heir in the will of a family retainer who also died in 1632.

Then in December 1634 Joan Steere herself died. George Steere recorded her burial in the Newdigate registers, describing her first as her father’s daughter, and only secondarily as his wife. He distinguished her burial from the others he recorded that year by writing it in Latin.

He also erected a plaque to her memory on the chancel wall, that still survives:

HERE LIETH YE BODY OF IOANE DAVGHTER OF THOMAS SMALLPEECE

& LATE YE WIFE OF GEORGE STEERE PARSON OF THIS PARISH

SHEE DIED DEC: 7 AN: DOM: 1634 & EXPECTETH A BLESSED RESVRECTION.

This Calvinist confidence in the resurrection of the elect was shared by her yeoman father, who in his 1626 will declared himself ‘one of the Elect of God’.

Four and a half years later George Steere married again. His new wife was Sarah Bristow, the widow of the rector of the adjacent parish of Charlwood, who had died a little under two years previously. This second marriage took place in Lindfield, Sussex, but again George Steere included a record of the event in the Newdigate marriage register too. Sarah Bristow had been only modestly provided for by her husband. Her husband in his will, written shortly before his death, evidently entertained the hope that she might be pregnant, but if not most of his lands in Charlwood and Horley were to be distributed amongst his family, with Sarah, who he made his sole executor, to receive only their household goods, 36 acres of tenanted land and “the English books she wants”. Sarah Steere was to survive her second husband, and she was his executor too when he died in 1662. She was doubtless already well-versed in the duties of a clergyman’s wife, and in 1655 she appears, alongside her husband, as a witness to the nuncupative will of a Newdigate yeoman.

George Steere had no children by either of his wives, so when he came to the end of his long life he was able to distribute his worldly resources to such recipients as he chose. He of course made decent provision for his wife, mainly by means of annuities charged on the properties he bequeathed for charitable purposes, and he left modest bequests to a long list of other relatives and friends. However, most of his estate was used to develop three new charities, all educational in nature, and perhaps reflecting older charities that had enabled him to pursue his own career. Two were to benefit Newdigate, and both of these had been established within his own lifetime. The third was to benefit Lewes, where he had started his clerical career.

Each of the three charities George Steere created was to operate in a different way. The first one listed in his will gave a small piece of land belonging his own house on which he had built a schoolhouse to the inhabitants of the parish of Newdigate, on condition that they keep it in good repair. His house and the rest of its land was bequeathed to his second wife Sarah for her lifetime, and thereafter to members of her family, subject to a requirement that the owner paid £6 13s 4d every year to cover the education at the school of four young boys “of godly poore parents”. The school received additional endowments, and has been both rebuilt and relocated, but survives to this day as the Newdigate Church of England Endowed Infant School. Can it possibly be a coincidence that Sarah Steere’s first husband, Rev John Bristow, had also built a similar school in his own neighbouring parish of Charlwood during his lifetime, and that he too by his will had endowed it with a piece of land that he owned so that three poor children should be educated there without payment?

The second charity mentioned was the Lewes one, where his property in the town was gifted to the inhabitants to maintain a poor student from the town or its surrounding rural area at a college of their choice at either Oxford or Cambridge. The third was similar in principle, but quite different in the way that it worked. George Steere had purchased a Dorking property, and from its annual rents was already supporting the maintenance of a student at Trinity College, Cambridge. This property he bequeathed to members of his own family, but they were to pay all the rents received to his wife Sarah for her lifetime, and out of that she was to pay £12 p.a. to the student at Trinity College. When this student completed his studies, the Exhibition at Trinity was to continue, now reduced to £10 p.a. and limited to a maximum tenure of 4 years. The successive beneficiaries were to be young men from Newdigate or the surrounding area, chosen by the ministers of Newdigate, Dorking and Ockley in Surrey and the minister of Rusper in Sussex.

Sources: L.F. Salzman, ‘The Town Book of Lewes, 1542-1701’, pp.86-87; Colin Brent’s Lewes House Histories; J. Venn, ‘Alumni Cantabrigiensis’, available at https://venn.lib.cam.ac.uk/; Clergy of the Church of England Database, available at https://theclergydatabase.org.uk/; FindMyPast; Newdigate & Charlwood sections of the Exploring Surrey’s Past website & Victoria County History of Surrey; ESRO SAS/BB 23; George Steere’s will is TNA PROB 11/308/645; John Bristow’s will is TNA PROB 11/174/531; The website of the Newdigate Local History Society contains several views of George Steere’s house in Newdigate.

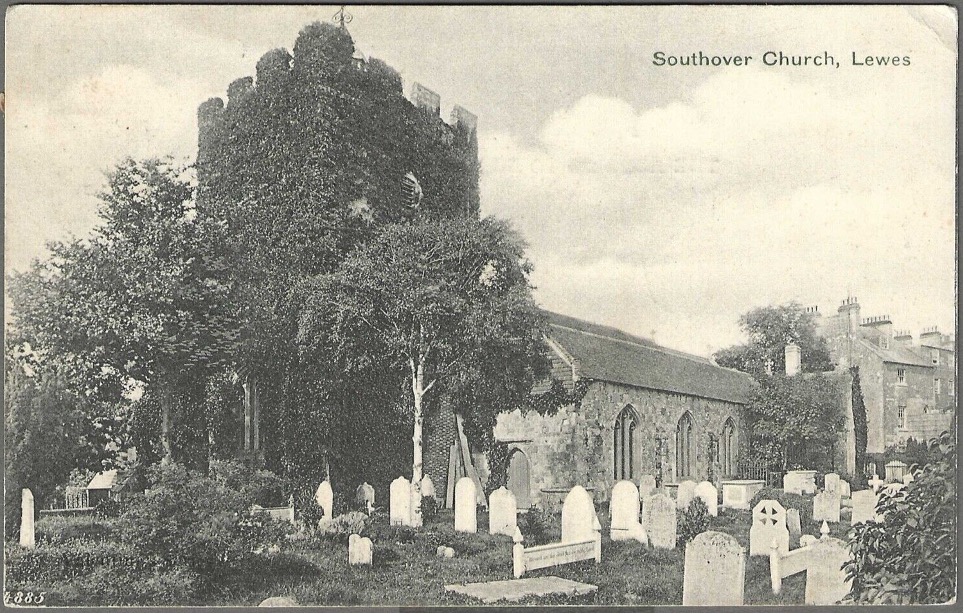

5. A well-travelled postcard of Southover Church

This postcard featuring Southover church by an anonymous publisher, offered for sale recently on ebay, was sent from one end of France to the other to mark the arrival of the New Year 1905.

6. Ouse abuse (by Chris Taylor)

Anxiety about discharge from sewers into the River Ouse is not new. There was no sewerage in Lewes until the second half of the 19th century. Before then, cesspools, requiring frequent emptying, were the means of dealing with human waste, with much of it ending up in the river. The Sanitary Act of 1866 obliged local authorities to provide sewerage systems, in response to which the town’s Improvement Commissioners installed the first sewer in the High Street, at the same time as Bazalgette was famously and similarly engaged in London. The Borough Council extended it to include St Anne’s in 1888 and in 1891 Arthur Holt, the Borough Surveyor, devised a comprehensive system to encompass the whole town. The scheme was implemented in stages: Paddock Valley in 1893, Southover in 1895 and Cliffe in the early 1900s. All these sewers were designed, via a series of outfalls at intervals along its banks, to discharge raw sewage into the Ouse.

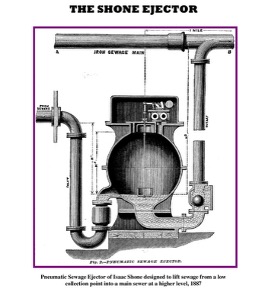

The Cliffe was left until last because its flat topography inhibited the fall required for efficient sewerage. Replacing the ancient culverts, installed originally to deal with flood water, proved expensive. The council’s scheme involved installing two electrically-powered pumps – Shone Ejectors, placed at the entrance to Newington’s coal merchants’ wharf in South Street – to lift the sewage to an outfall into the river near the gasometer. To pay for it the council had to approach central government – the Local Government Board (LGB) – for approval to borrow £7000.

The County Council objected to the loan. Responding to complaints from neighbouring local authorities, Dr Foulerton (sic), the Medical Officer of Heath for East Sussex, reported in July 1903 that the discharge of sewage at Lewes was the likeliest cause of the recent prevalence of typhoid fever downstream in Newhaven and Piddinghoe. The County Council applied to the LGB for an order declaring the Ouse from Barcombe Mills to Glynde Reach to be a ‘stream’ within the meaning of the Rivers Pollution Acts of 1876 and 1893, which would make the discharge of solid waste into it illegal.

The County Council put its case to LGB inspectors at a three-day inquiry into the matter in October 1904. The Borough Council conducted a vigorous defence, arguing that the prevalence of typhoid at Newhaven could not in any way be attributed to the pollution of the Ouse by sewage from Lewes:

- there had been no outbreak of typhoid in Lewes itself

- Newhaven had been unaffected by the last severe typhoid epidemic in Lewes in 1873-75, so river pollution could not have been to blame

- sewage from Brighton (population 160,000), routinely discharged into the sea 2 ½ miles west of Newhaven harbour, was a far more likely source of infection, a factor not considered in Foulerton’s report.

The inspectors dismissed the County Council’s application. But their report insisted that the Borough promptly take remedial measures to eliminate ‘the highly objectionable and possibly dangerous condition of the river in the neighbourhood of Lewes, occasioned by the discharge of crude sewage.’

Faced with the need to improve the condition of the river, the council proposed a different approach. All the town’s sewers were to be diverted via new intercepting pipes to a central point, where the sewage would be screened and pass through sedimentation settling tanks. It would then be discharged into the river, at ebb tide only, through a single outfall situated a little below the mouth of the Cockshut at Southerham. Connecting the existing main sewers, building several new tributary sewers and buying the 19 acres of land for the outfall works would require permission from the LGB to raise another loan, this time of about £18,000.

Dr Foulerton was not impressed. The County Council objected once again on the grounds that the scheme contained no plan for the proper purification of the sewage. The sedimentation tanks, they argued, would remove no more than 50% of the solids, with the rest destined to enter the river. It was not possible for the town’s waste to be taken the seven miles to the sea on one tide: it would inevitably be carried back and forth, with much of it deposited on the river banks, presenting a high danger of infection.

Consequently the LGB held another inquiry in October 1909, at which the Borough Council stressed the degree of improvement the new scheme would deliver. The screening, the sedimentation and the sluicing in the tidal storage reservoirs, would mean that the condition of the effluent reaching the river would ‘leave little to be desired.’ No current method of purification was capable, they claimed, of rendering sewage entirely harmless to health. Rather than spend a lot more money on sewage treatment works with no guarantee that the resulting effluent would be free of disease, it would be better to persist with the planned scheme, monitor its effects and concentrate on improving the drainage system across the town, where there were still old sewers requiring replacement.

Again, much to the surprise of many at the forefront of work in sanitation, the LGB approved the loan and the scheme went ahead. Large quantities of raw sewage continued to be routinely discharged into the Ouse until biological purification processes, filtration and disinfection were adopted later in the century and the outfall site became Lewes Sewage Works.

Sources: Public Inquiries into pollution of the Ouse, 1904, 1909 (ESBHRO: NRA/12/2 and c/c/74/1/21); Lewes Borough Council Sanitary Committee minutes (ESBHRO: DL/D/169/5); Journal of the Royal Sanitary Institute Dec. 1912 (ESBHRO: AMS6042/1); East Sussex News 5 November 1909; CIBSE Heritage Group website (Shone Ejector image).

7. Merging the Lewes and Chailey Poor Law Unions

In November 1897 there was a public meeting at Newick to discuss the Local Government Board proposal that the Chailey Poor Law Union and some parishes belonging to the West Firle Union should be amalgamated with the Lewes Union. Newick residents were opposed to the change, but in March 1898 the proposals went ahead anyway. Two months later there was a large increase in the poor rates that Newick residents had to pay.

Thereafter the Lewes Union Workhouse in St Anne’s parish was closed, with its residents moved to spare capacity at the Chailey Union workhouse built in 1873 on the southern end of Chailey Common (in East Chiltington parish). The poorest Lewes residents were thereby moved further out of sight and out of mind.

Source: Tony Turk, ‘A Victorian Diary of Newick, Sussex, 1875-1899’. The same parishes of the Chailey & West Firle Unions remain part of Lewes District Council today.

8. Treasurer’s Final Report for 2024/5 (by Phil Green)

John Kay 01273 813388 johnkay56@gmail.com

Contact details for Friends of the Lewes History Group promoting local historical events

Sussex Archaeological Society: http://sussexpast.co.uk/events

Lewes Priory Trust: http://www.lewespriory.org.uk/news-listing

Lewes Archaeological group: http://lewesarchaeology.org.uk and go to ‘Lectures’

Friends of Lewes: http://friends-of-lewes.org.uk/diary/

Lewes Priory School Memorial Chapel Trust: https://www.lewesprioryschoolmemorialchapeltrust.org/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LewesHistoryGroup

Twitter (X): https://twitter.com/LewesHistory