Nevill Memoirs > Sid Larder

Click on images to enlarge | Download this article as a pdf document

CHILDHOOD

I was born on 23rd December 1944 at Southlands Hospital, Shoreham. My mother, Ivy Larder née Brown, was born in Lewes. The reason I came into this world outside Lewes was because my Mum had TB and needed extra care. It turned out that not only had she given me TB, but I was born with two club feet which meant both feet were deformed.

My Mum had three sisters and one unofficial brother, taken on by my Gran from next door because they had too many children. They all lived with Gran (Susan) and Grandad (Walter) Brown in a two up two down house in Spring Gardens at the bottom of North Street: one gas light, one cold tap and the loo at the bottom of the garden – posh name for small yard.

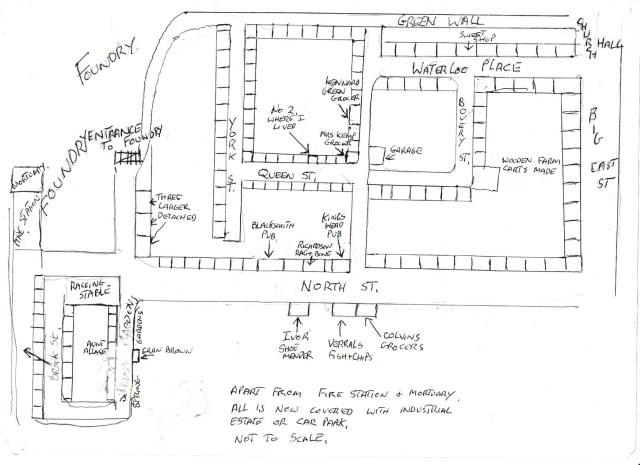

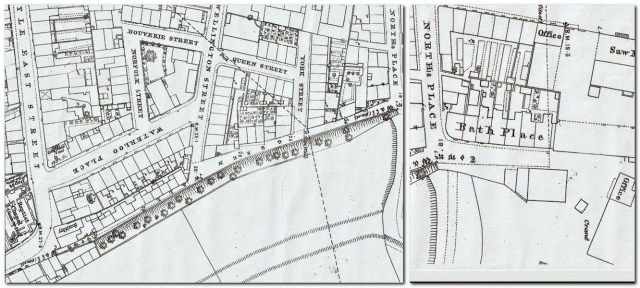

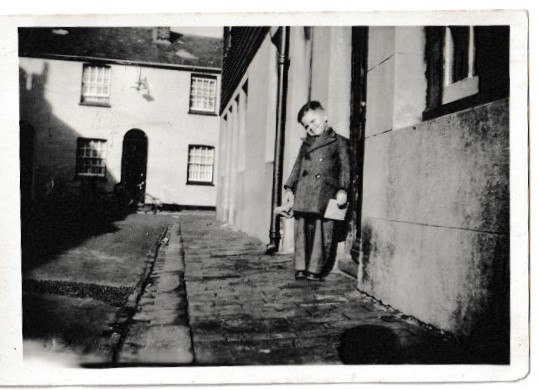

This area of Lewes was made up of several streets serving the Foundry next to Green Wall. I remember it having two pubs, one Rag and Bone (man), one fish and chips, two grocers, one greengrocer, one shoe mender, (one legged Ivor – could never understand how he could ride a bike?) one sweet shop, Fire Station, with town mortuary next door and one Racing stables. The Foundry was a big employer. My earliest memory, when I must have been only about three, was looking over Green Wall to see it all ablaze. By this time, we were living at no. 2 Queen Street. This was one of many streets in our area: Waterloo Place (which is still here,) York Street, Queen Street, Bouverie Street. Spring Gardens, Lancaster Street, North Street and Brook Street. All these were two up, two downs – nothing less than slums, loo at the bottom of the garden. Queen Street, York Street and one side of Waterloo Place seem to have been at the top of a small valley: front door on the road, kitchen and coal cellar below. Go to the end of Waterloo Place, look into what is now North Street industrial site; you will see quite a drop from the road. We had a door at the back leading to a small yard with the loo at the end. Dad kept rabbits and chickens for the pot.

I had a happy time here, somewhat restricted, not being allowed to play rough games due to my problems, but I joined in with the other kids playing hide and seek round the Pells at night. No worries about paedophiles or other trouble then – older kids looked after the younger ones and grownups kept an eye on us all.

As an only child I spent a lot of time on my own, especially when I couldn’t walk properly. Adults didn’t play games with us. Dad came home and listened to the radio; Mum was often ill in bed. Neighbours would make sure Dad, Mum and me were OK.

The light of my week was in Queen Street. 6 p.m. Saturday Dad would take down football results and we would then go off to the Cinema de Luxe. I had already been to the a.m. children’s pictures at the Odeon in the Cliffe. I would have had 9d, 6d to get in and 3d for a lolly – less than 5p today.

Dad was unable to look after both of us and work at the same time so I was taken in by my Aunt Ethel in Landport. It was either this or I would have gone into a home. I went to Aunt Ethel because she also had an only child, Richard, two years younger than me. Dad, because of Mum, was given a pre-fab almost opposite Aunt Eth. It was decided to leave me there because Dad only had two bedrooms and his Mum moved in to help look after Mum. Aunt Eth had three. All my aunts worked cleaning and other small jobs mornings and evenings and so had no time to play with us

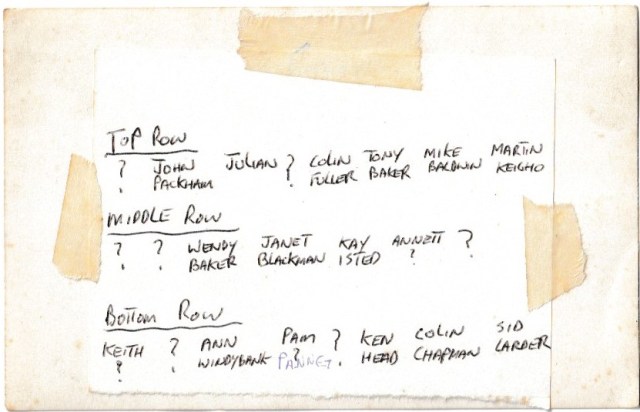

EARLY SCHOOLING

My schooling, such as it was, started at the Pells when I was five. Day one didn’t go well – was afraid to ask, so wet myself. Mrs Banks, my first teacher was so kind as were Mrs Cripps, Miss Bingham and Mr Turner, our headmaster. I was moved to Wallands in 1951 when it opened. The headmistress refused to let me in the hall, fearing my boots would damage her floor. My aunt was furious and managed to move cousin Richard and me back to the Pells.

While I was at Aunt Eth’s it was discovered I had TB and, as she had a son, it was thought best I went to live in South Street with Aunt Carr (Caroline) and Uncle Joe who were childless. The family always met at Gran Brown’s house Sunday afternoons. She had the only TV in the street. When it was time to go home Uncle Joe said “you had better come home with us but on the way we must, or at least I must, go to ‘Church’.” This was the first I heard about it. Gran Brown’s house was by this time also in Landport. So, we walked (me in a push chair, feet in plaster of Paris) to North Street. We stopped at the Blacksmith Arms on the way. He then said this was his church and I was not allowed in.

While I was at the Pells, at the age of about five, I started going to Chailey Heritage. I would go every month to have both feet in plaster of Paris. While it was still wet my feet were forced into what was supposed to be a normal position. Needless to say, this was painful – getting worse as the month wore on as my feet were growing and being restricted. After each visit to the hospital, I was not able to walk or even put pressure on my feet until the plaster had gone hard. A special sole was fixed at the same time so after three days I could walk after a fashion. So began my lack of education as I was not allowed to leave the house. Uncle Joe had to carry me about the house. When I could walk, I had to be taken to school in a push chair. No wheel chairs – couldn’t afford one. At school the teachers were aware of my pain and I was sat at a two-person desk. The other person moved. I was allowed to sit with my back against the wall. I did so much crying I was often sent home with one of the teachers.

Aunt Carr, if Uncle Joe was working, would take me to work – at that time cleaning at the Nat West Bank. I had a great time with lots of paper clips and pens.

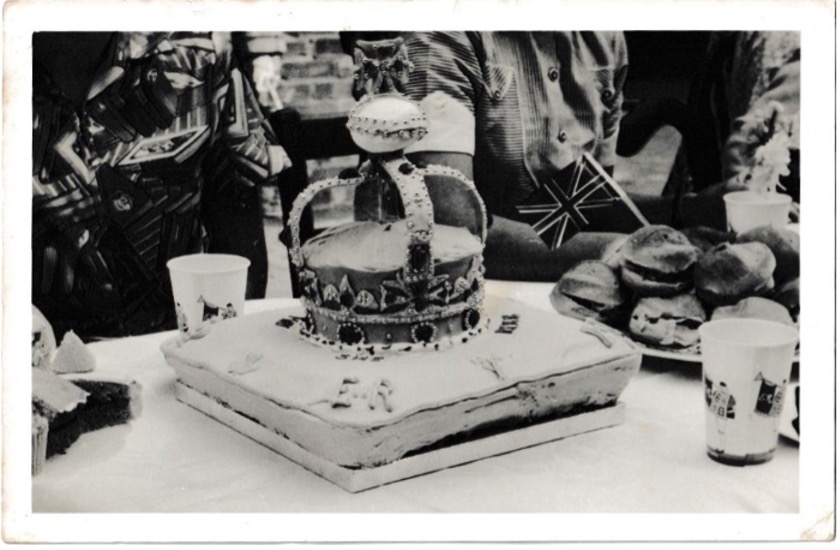

To this day I hate all games, never been to football or cricket, at Xmas was usually given a board game for two or more players. Try playing with only me – at least I always won! I would also get a comic album, but as I couldn’t read, I only looked at the pictures. If I asked my Dad what the speech bubble said he would say: “if you can’t read it say wheelbarrow.” I had so many wheelbarrows in my life. It wasn’t till much later that I found out Mum was illiterate, Dad almost. So, not one reading book in the house. We had the Daily Mirror paper but Gran (Dad’s Mum was a tartar) would take it away from me saying it was not for boys to read. In 1952 the king died and so did my Grandad Larderin Portsmouth. 1953 was our late Queen’s coronation. Aunt Carr told me how they had decorated Spring Gardens for King Edward VIII’s coronation. They didn’t have much money so they made their own bunting out of newspaper they had coloured. A picture is still about – not with me though. So, we set about our own house – 79 South Street, now called Bargemasters House.

Photographer E.A Meyer 23 High Street, Lewes

While I was living there and my Dad was back in Queen Street. I was allowed to go to two street parties, Queen Street and South Street. We had to pay 6d per week for the party till 2/6d was paid. They couldn’t have been on the same day as I remember them both. The Queen Street party was held in Bouverie Street I was upset at the games after tea. I was not allowed in the sack race. Plasters again.

At South Street it was held in The Thatch House pub car park. They manhandled the pub upright piano out and Betty Ford played and everyone danced. In the evening the Bonfire Societies held a joint procession from Morris Road. to the fair ground, now the Gallops. We, as usual, were late and at the back of the procession. There was a great crowd. Not to be outdone Aunt Carr had one arm, Uncle Joe the other, me in the middle, feet not touching the ground. No road closures then so they thought it best to hop on a bus that was in front. Never made it to the procession but, still in my Valencian costume, we made it to the fire site. Many years later I was talking to Eric Winters who I knew had had a hand in it. I told him I knew what the set pieces were.

He said I wouldn’t be able to remember. I told him: Castle Gate House, Portcullis went up, Queens’ Picture was illuminated.” Not a word from Eric!

All the while I lived at 79 South Street Aunt Carr looked after Uncle Joe’s uncle who was 95 then. He often baby sat me. He was a great person – so interesting. He was a shepherd by trade, here on the Downs. He was also probably the last poacher in Lewes. His name was Bobby (Henry) Baker. Stories he had of catching swans for their feathers for the hat trade and also about the odd lamb-skin pegged out in our walk-in attic, curing. He had his own small boat on the Island, created by Cliffe Cut since filled in – now the boat yard in South Street. There were also one or two pig sties. There were pig clubs. Small pigs were bought (pinched) and everyone in the club helped feed and look after them till the time came. Then they would be shared out.

Another of his side lines was “bobbing” – catching eels. I still have his own eel spear. Bobbing got its name from two long poles. One had at tin bath floating at the end, pole through the handles. The other had a metal rod fixed vertically at the end with a bunch of worms. He would have an oil drum filled with soil where he would “grow” his stock of worms. When needed he would thread a string lengthways through the worms, gather them into a bunch, attach them to the iron rod, place this pole next to the bath and press into the mud. When you lifted it out you would have eels on the end. They caught their teeth on the string. I hated watching him skinning them alive when he got them home. Sharp tap over the bath and they would fall inside and not be able to get out. Years later, when Bobby was well over a hundred and I was on British Airways, I would take foreign sweets for him.

In York Street there were several families of gypsies. Mr Smith had a Heath Robinson style hand cart which he took round sharpening knives etc. At Christmas he made holly wreaths. Mr and Mrs Cooper had two daughters: Neta and Amy. Mr and Mrs Russell had one son and one daughter called Phoebe. Mrs Russell made what was then classed as artificial flowers: bits of coloured wax fixed onto twigs. Mr Russell had a small flatbed lorry. I only remember it twice. First when Granny Russell died – she left the street covered in wreaths. The other time was when they were hop (or fruit) picking when it was loaded with essential items like mattresses and pots and pans.

We all got on like a house on fire. No prejudices then. Phoebe took me to Compton’s Yard between the Fire Station and the river where there was an encampment complete with horse-drawn caravans. One of Phoebe’s relatives lived in one and I was accepted as a friend. The lady was quite old and made us tea over an open fire, while smoking her pipe the whole time. This was the first time I saw corn on the cob. They had a small patch next to them.

Other friends in York Street and Queen Street were Steve and Teddy Thompsett and Enid and David Beal. He was handicapped and worked at Clayhill Nurseries in Malling Street. There were two families of Parsons including Rod and Kathleen Parsons. We would all play together, sometimes at the “Black Sand”. This was next to the Pells Pond and the Pells swimming baths. It was large heaps of black sand – the spoil of the Foundry after being used to make moulds.

After the Pells School I went to Mountfield Road School. Mr Smurthwaite was the headmaster. I was into music and in the school choir. We put on HMS Pinafore and, as we were an all-boys school at that time, I ended up as a girl, crinoline and all. We all went to Canterbury to sing in the cathedral with their own choristers. We were not on until evensong so we were allowed to have a look around during the afternoon. We found a tea shop where cakes were 6 pence each. A cake stand was put on our table and you paid for each item. Me being me, I collected money from my mates and every time we ate one, I put 6d to one side. Unbeknown to us we had been watched with amusement. A gentleman came over and gave us 2/6d: enough for one cake each. Back in the cathedral some bright spark had found a joke shop and dropped a stink bomb in the middle of the service. Later on, the headmaster gave us a dressing down as no-one owned up.

MY TIME AT CHAILEY HERITAGE

But I spent a great deal of my childhood in Chailey Heritage Craft School and Hospital. This was started by Dame Grace Kimmins as a charity for disabled children. This was several years before the NHS was founded. She herself raised the enormous sum of over one and a half million pounds. (The wage for a man was no more than £1 10s (£1.50) per week) The Heritage was at three sites on the common, not all at the same time. Site one on the A 272, which has the church – St. Martins, I think. This housed teenagers upstairs. The ward ran right along the building. Downstairs was girls. This site also was where school buildings were. These were for the boys, disabled but not seeking medical treatment.

I was in a ward for boys who needed treatment. The boys all had numbers for identification of clothes, shoes, towels etc. I was No.23. At the back of the building was double doors which opened onto a large veranda, square in shape in which the beds were put when it was dry. These beds were high, about a yard off the ground with iron strips across the base. On the top was a mattress of horse hair. At this time TB was being treated, and this was done by us all sleeping outside except when it rained. We were only allowed a loin cloth, no other garment, night or day, and an over sheet and one pillow in spring/summer. In winter we had a shirt in the day and pyjama top at night and one blanket!

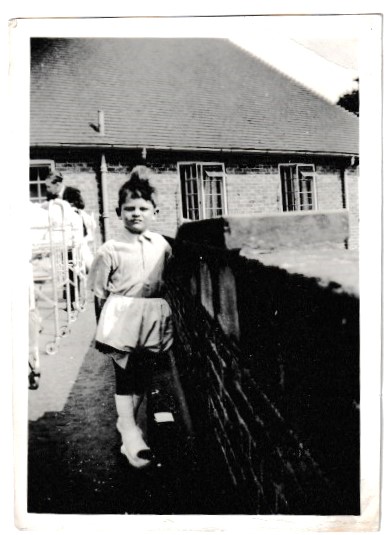

While I was first at Chailey Heritage we were moved lock, stock and barrel from the old heritage building to the new hospital on the other side of the common, not far from Sheffield Park. I remember it well. We all had to have a bath as we were going into a quite modern building. When we arrived, we had to have another bath as we were going into a new bed. Up till then I only had one bath a week. We were on the ground floor called Boys Ward. Upstairs was the infants ward called Princess Margaret Rose Ward. I have a photo of me at about seven when I was in Princess Margaret Rose ward. I can say at one time or another I spent time in all the different sites which made up the Heritage. Both Princess Margaret and the Queen Mum used to come to see us at times.

Nothing changed! We still had numbers. The older boys were still outside almost naked night and day. I remember one night, when I was a bit older, we had an enormous storm. As there was only one orderly on duty pushing the beds (which had wheels) into the ward, needless to say, most of us got soaked.

This third site was St Georges. It was in the middle of the common, between sites one and two. It looked like a monastery with a windmill to one side, said to be the middle of Sussex. On the inside it looked like Hogwarts, with dormitories (not wards) in the arms. The centre was a very large hall. Three rows of tables lengthways with a top table for matron, Mr Gallespie (priest of St Martins) plus other staff. Behind them was an almost floor to ceiling stained glass window. The whole room looked like Hampton Court.

St Georges was where boys were sent, just like boarding school, because disabled children didn’t go to ordinary school. We lived in St Georges and went to classes in site No.1 where the church is. We were treated just like ordinary boys: we had our own pet corner with mice, rabbits, chickens and such like. Every day we had to feed them and clean them out. Those that could, played cricket. There was a room where we could do simple carpentry in the evenings. Opposite was a sunken building – I think it was an old air raid shelter – where older boys could play table tennis and other games. I only ever went there on Sunday evenings where we would have our own cinema with all up-to-date films.

Visiting was still once a term but we could be taken out. I remember one Christmas term we were given tickets to a special performance of Bertram Wells Circus at Olympia in London. We had a small convoy of coaches, each with picnics. We were not the only ones; the whole audience was made up of disadvantaged children of one sort or the other. On our return we all had a bowl of tomato soup. I actually remember my time at Chailey Heritage as being quite normal and happy.

We had one or two special boys. Most had been placed in Chailey Heritage as they were an embarrassment. I remember a Saudi prince there. When we had a visiting day his Dad, the Sheik, didn’t come but his ambassador did. He brought us all a gift: a neck-tie. Dressed to the nines – loin cloth and tie! The thought was there.

The lad next to me, Keith by name, told me he was sitting on a fence, fell backwards into a river and caught polio. He was unable to do anything for himself but, believe it or not, he was the ward bully. The other lads treated him with care, giving him their one sweet but I got on well with him. Any nonsense, I just pushed him flat in the bed and he would burst out laughing. He couldn’t even sit up on his own. Believe it or not he was about 12 and a smoker. His Mum sent cigs and matches each week. He would pull the sheet over his head when we were going to sleep and smoke. He had an old tin where he got rid of the ash. The orderly must have known but turned a blind eye. The head orderly used to let him roll cigs for him. One day Keith put a bit of Jet X Fuel in the middle of the orderly’s cig. (We had a spate of making model planes) When next day Mr Turner came on duty all he did was laugh. When it exploded, he dropped it, so no problem.

When in the Boys Ward we had two boys locked in two rooms above, with loin cloth taken away. They were being punished because they had run away – if you can run away in a wheel chair! Not bad though – they got to Scaynes Hill before being picked up. We might have been disabled but still did most things ordinary boys got up to. Another thing we did: a path ran between Babies Ward and the staff canteen. Nurses would go between these, always in bunches of six or seven. A tree was overhanging the path so we put a string over a branch with a large make-believe spider on the end. This stretched across to our ward. When they were underneath, we would drop it. Great fun seeing them scatter. We didn’t get into trouble – the opposite – we had become quite famous. Funny watching them all avoid the tree even when we had to take it down.

Visiting was almost non-existent in the early years. We were only allowed one visit per term from 2 until 4 o’clock. I spent several Christmas days there. My Dad dropped my presents off but he was not allowed in the ward – just a wave through the window in the door. One Christmas eve my Dad brought my gift. It was confiscated. It was a chemistry set, and me being in bed didn’t mix. Same went for Miss Bingham who brought me a basket of fruit; she also made do with a wave. All sweets and fruit were taken away and put together and each day after lunch and our hour-long compulsory nap Sister came round and we could pick out a sweet from her tin. She would say “one for you, two for me”! No wonder she was such a large lady. But it was fair. Some children were abandoned due to their families not being able to cope. I was lucky. Some boys had horrendous problems. Not including the time at home with plaster on my legs, I spent several terms there – from a few months to two sessions of over a year each. The last of these I had the biggest operations when I was not allowed out of bed for ten months.

We lived in St Georges and went to classes in site No.1 where the church is. Our schooling was basic. When on the ward we were not able to be in a proper class. All the beds were in a line outside. There was no blackboard, only one teacher and an assistant going from bed to bed. Imagine about 25 boys aged 11 to 15, all with very different abilities and mental capabilities and only two teachers and a nice old lady who taught us sewing. No such thing as one to one. St Georges was where boys were sent, just like boarding school, because disabled children didn’t go to ordinary school. No two children were learning the same thing. No games, no group activities. In the afternoon we did sewing and basket making as this was all some of us could do. It was very much do it yourself. I was given a book and it was expected I could read as I was fortunate in that I was able to walk. (sometimes)

Most kids (still only boys here) were not expected to do well in the workplace so we were taught basket making, sewing and painting for the most able. When I was about to leave in 1960, I was told by a Mr Shephard, the Youth Employment Officer, that I was “factory fodder”. I must only have a sitting down job. Red rag to a bull! My last year at Chailey was on Boys Ward. I went from site to site depending on what operations I had to have. Both my ankles were surgically fused and now I have no movement at all in both feet. In the last year I was not allowed out of bed for 10 months. During this time my Mum died of TB. I was given permission to go home for a few days for her funeral only if I promised not to stand or try to walk. They lent me a wheel chair and my Dad had to carry me at other times.

My birthday is in December and I was due to leave when I was 16. I was desperate to be home for November 5th so I made up a story of a family wedding. They said as it was only one month short, I could leave on November 4th. On the 4th the orderlies joked about my going to Bonfire Night and said it was cancelled due to flooding. I didn’t believe them until I got home. Would you believe it? One of the societies took their fireworks to Chailey Heritage!

LIFE AND WORK IN LEWES AFTER CHAILEY HERITAGE

As I said, I left on Friday November 4th. By mid-day Saturday I had been for an interview at the Crown Hotel and got a job in the kitchen. I asked if I could start in two weeks as I had been in hospital for a year. They said yes. I had two weeks holiday at my Dad’s family farm in Glastonbury and started work at the Crown Hotel in Lewes on the 19th November 1960. I thought I was going to learn to be a chef. How wrong I was! I had to work 8 – 4pm EVERY day – no day off. I saw the youth employment officer – the one that said I was factory fodder. He told me if I worked an extra hour each day, I could then have one day off. My wage was £3 per week.

The hotel was the original Fawlty Towers. The family were the proprietors. The boss was nice but very large and liked his food and drink. His room was at the front. His wife thought she was upper crust, insisted on being called Madam. Her room was 100 yards away at the back, with back stairs leading outside, which came in handy as she always seemed to have someone there with her – never her husband. She didn’t give it a thought asking for two breakfasts. On one occasion it was the barman.

We had a steady stream of chefs. I was expected to know at the age of 16 how to cook: mostly breakfasts as I was on my own till about 10. It was a lovely dining room; old but well looked after. It was a shame that the waiter did not come in until 10 either so I had to wait at table and cook. To get between the kitchen and the dining room I went out of the kitchen door and up three steps into the dining room. When a guest came in, I had to take my kitchen jacket off, put on a waiter’s jacket and take the order. Then the reverse procedure: put the food in the serving hatch and repeat the whole thing. In 1961 the Pelham Arms burnt down and we had the landlord and family staying. He saw all this and said to me: “When the Pelham is ready there is a job for you.” I wish I had taken it.

Apart from Christmas Day, which I worked as usual for no extra money, I never saw any of the family eating together. They all took trays and went their own ways. The youngest insisted on having his food while on the loo. He was about nine. When I told him it was wrong, he just said: “My Dad owns this hotel – you do what I want.” Madam was nearly always with her upper crust friends. None of them seemed to work but all ate and drank there. I never saw any money change hands. The boss always got drunk at midday and would go to bed. I would have to call him before I went home. One day I did this to find he had wet himself in bed. I was asked to help clean him up which I did. Other jobs I had to do was collect the brat from school, do the family washing as well as clean the kitchen ready for the evening meal. The eldest son sometimes had to make this as we might not have a chef at that moment. He was not at all worried about cleanliness. One day he was doing lunch. The fat in the fryer spat at him, so he spat back into the pan. I was supposed to have my lunch provided but thought better not to. One of my morning chores was to pick over the part cooked chips, which could be several days old, so the blue ones had to go. We had a floor to ceiling double freezer. One day there was about four inches of water in the bottom. It had defrosted. Laying in it there were about six whole dover sole. I was about to ditch them but the boss stopped me and told me to soak them in vinegar. He would get the chef to put on a special that evening!

As I said, I worked that Christmas. It was quite funny. They were, the family that is, all round the table. The waiter was in as usual. Madam had her hangers-on as usual. The boss didn’t seem too worried. My lasting impression was of the waiter flat out on the floor: he had had more than his usual. The family just laughed.

The Hotel always had a shortage of cash. I would be sent over to Coppard and Likemanbutchers, next to the White Hart, for the meat but was sometimes told “No, not until the bill is paid!” This was the same at the dry cleaners in Station Street. This was the same for our one permanent guest. His ticket was always refused. His money mostly went to the betting shop. I know because I had to put the bets in. It was beneath him to be seen there. Needless to say, he had to be addressed as Major.

I didn’t last the year out. I had had enough after eight months and gave my notice in. The boss offered me a 50% rise which I refused. It would have been £4.50s. Just as well I did. Early in 1963 the Crown was bankrupt. All the time I was working there I lived with my Dad in 28 Crisp Road, Landport. My Mum had died when I was in Chailey. My Dad’s Mum, my Gran, had moved in to help look after her and my Dad. She stayed on until he re-married in 1965.

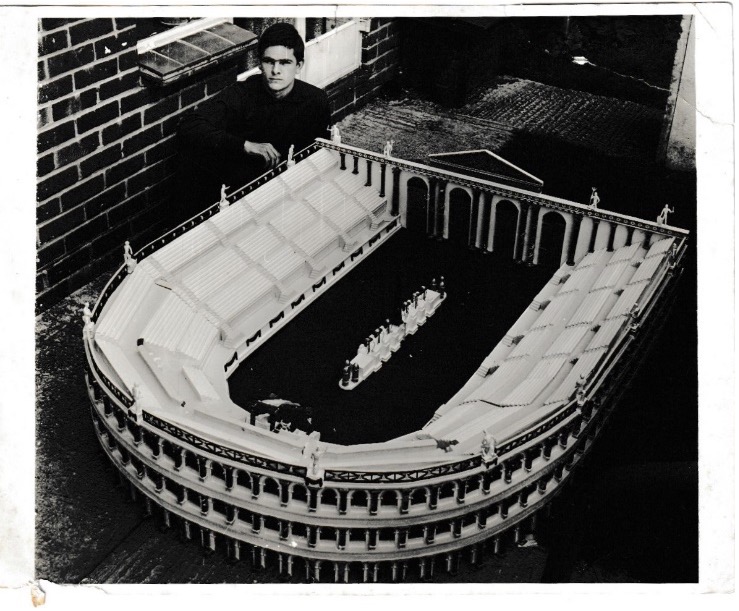

Sussex Express August 1954

Because I was on my feet all day at the Crown I had to rest in the evenings. I started making a balsawood model of a Roman circus. This got out of hand and ended up 5 feet long. After I left the Crown, I met up with my best mate from Mountfield School and we started going to Brighton every Saturday afternoon. We had our hair styled and then went down to West Street to the Regent Ball Room. As it finished after the last train had gone, we walked from there to Lewes – took us all night. After that, when we missed it again, we would just sit on the platform and wait for the first train out. On David’s 21st he and I went to a Chinese restaurant where we had never been before. I said “I don’t think much of this” but he thought it was great. Then we found out you ordered several dishes and shared them. We had two. I was eating the rice; he ate the good stuff. All the big blockbuster films were shown in the Steine. I went five times to see Ben Hur, I liked it so much I bought the LP of music, even though I didn’t have a record player. I still have the record, still waiting for the player!

There were very few people like me with few if not nil qualifications but in the ‘60s there was no problem getting work if you wanted it. My Uncle Arch had an old family friend (that was as far as that went) who was also his drinking partner. Her name was Elsie Larkin: a very jolly, friendly person who was the supervisor at the Corona Soft Drinks firm which had a factory near Thomas Street. I had no problem with gettinga job and started the next Monday. Elsie was quite strict but always fair. I never saw her without some sort of hat and even at work she always wobbled on four-inch stilettos. They taught me how to drive a fork lift truck which I used in the factory. I would be sent out to load and unload our large lorry in outlying depots. They also had a small fleet of lorries for local deliveries. In 1963 the factory closed so I was redundant.

Jobs were still available so I walked into another one at Smith and Nephews Hypodermic needle makers in Malling Street. My job was to put very fine sand through the needles to clean them out. I had to do several thousand a day. Everything had been timed so no let-up – we worked to a bell. We started work at 8.15, had a 15-minute tea break, 1 hour for lunch at 12, a 5-minute tea break at 3 and went home at 5pm. But, despite what the Youth Employment Officer said, factory work was not for me.

One of my work mates was going into the army. What a good idea! I joined up in 1966. “What about your feet?” you might ask. I just didn’t tell them – red rag to a bull again! I had an interest in operating theatre work. While at Chailey our ward sister was also the theatre nurse. They only had operations every couple of months. When I was able to walk, she would take me to clean all the instruments. So, I joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. I did so enjoy it. I made it through the basic training and was just about to start the medical side but we had a scheduled foot inspection. One look at my feet and the M.O. asked me how on earth I had got past the Medical Board. I told them “I didn’t tell lies – I just didn’t tell them!” They were so impressed. Many of the other blokes were trying to get out and here I am trying to stay in. The commanding officer moved high and low trying to talk to the powers that be to let me stay. No – in the end I had to go. They let me stay as a guest of the army to watch my mates’ passing out parade. My discharge papers said “medically discharged” and they put me down for a war pension which I refused. Back home again, looking for a job, what should I find in the local paper: an advert for an operating theatre assistant in Brighton and Sussex County hospital. No qualifications needed; training on the job. In those days lots of paper was not needed. Pupils were only entered into any sort of certificate of education if you were in Grammar School or able to carry on into the Sixth Form. I wrote off, had an interview and started the next week. I had found the job which I liked. I was on my feet all the time but put up with it. My job entailed looking after the equipment being used. If it went wrong, I had to sort it out. As this didn’t happen very often, I had to do what we called “running”. This was getting things the sister needed when she was unable to get them because she was scrubbed up and couldn’t be touched. As Brighton Sussex County was a teaching hospital, we had trainee nurses who came in for a fortnight to see how it worked. They used to do the running but if they were not there I stepped in. No time had to be wasted. When nurses first came in, I had to stand behind them as they were watching the operation. Some couldn’t stand blood so they fainted. This was OK; I just grabbed them and let them down backwards – didn’t want them going into the surgeon.

I really loved this job but realised my education was not up to it. The sister insisted that I join the nurses in their classes. I already drew up drugs for the anaesthetist, kept an eye on the oxygen and nitrogen oxide and even sat in for the anaesthetist when he needed a pee. I was already holding a leg as it was cut off and having to take the bloody forceps off. Even though it was a clean cut everything had to be accounted for: bloody swabs had to be stuck on a frame with hooks and I would count them with the sister at the end. I decided I had to go before I made a tragic mistake. I gave my notice in and they tried to keep me. I didn’t tell them the real reason: I was afraid I couldn’t keep up with the nurses’ training. I said my Dad was moving to Wimbledon which he was, so no lie. But I could have gone back to Aunt Carr.

My lack of education has embarrassed me all my life. I won form prizes at Mountfield school because I knew all the facts but I never had the one-to-one help I needed to help me read and write in any of my schools. The needle factory offered evening classes for beginners but all the other students were doing GCE so I gave up. Since then, I have just about managed. I don’t know any grammar and only know arithmetic up to fractions. I love history and I am an avid reader now but I reckon I have trouble with 70% of the words. I just get the gist and make the rest up. When I am trying to write I squash together letters of words I can’t spell to cover up or I look for other words.

WORK FOR BRITISH EUROPEAN AIRWAYS

Before I gave my notice in I, with one of my mates, was giving one of the theatres a deep clean. We did a lot of this between cases. At the end of the day my mate said “I have applied to BEA as a steward on their airline.” This was before BEA and BOAC joined together. I then applied, had an interview and got the job which started with six weeks training at Heston, near Heathrow. BEA found me accommodation near Heathrow. The landlady was a right tartar. I shared a room with another steward. We only had access to our room and a front door key. Every other room was locked. At weekends we were not allowed to stay in the house after breakfast. I used to go back to Lewes for my days off, staying with Aunt Carr. Once I started flying there was no such thing as a five-day week. It was impossible to live in Heston so I went and stayed at Dad’s in Wimbledon – a bit of a drive but I had my car.

After two years BEA wanted to open a base at Gatwick. They had aircraft going in and out but none based there. We were licensed by the CAA to fly three types of aircraft. I was licensed to work on Comets (the first jet airliner), Viscounts and Vanguards. We had quite tough exams each year to make sure we knew where everything was. If you failed you were grounded till you passed. Most people think stewards are just to dish out food and drink but we had to know where every type of emergency equipment was and how to use it: water training, how to inflate a life raft and where the equipment is stored. Our first aid kits had everything you might need. The crew are the only people licensed to give morphine injections and how to record it.

We had medical refreshers every year. When you are 30,000 feet up it is no good opening the door and shouting “Help”! We got the basics: recognising heart attack and treatment right down to delivering babies. I realised that one expectant mother I had was having a miscarriage. I asked if we had a doctor or a nurse on board. We were coming from the US. Over there they will not help you: if something goes wrong, they can be held responsible. A nurse made herself known. I told her I knew what her situation was but would she tell me if I was doing the right thing. I had already got the lady in one of the galleys, on the floor with her feet up. It is quite simple most of the time – mother nature takes over. The funny thing was, I went and saw the father to be and said he might like to come down and reassure her. He said he would ONCE HE HAD BOUGHT HIS DUTY FREE! I had quite a few minor things: several heart attacks and even one attempted suicide. I even got an award for saving a man’s life-giving CPR. I got £25 for that: three weeks’ wages.

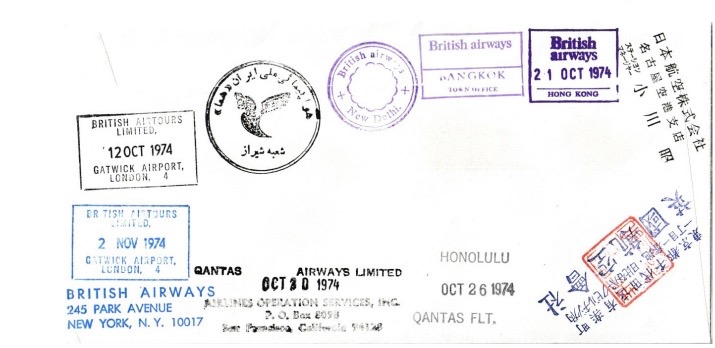

All told I did 26 years. I went all over the world. In the 60s package tour holidays were only just starting; most of the work was with the rich and business people. So, there were not many flights each day or week. We would go to the Caribbean and have to wait for the next plane to come and take them home.

We sometimes had a week off there. With all the time off we did all the usual – on the beach in the Bahamas and Hawaii. I have always liked history and was able to go to wonderful places. I visited Jerusalem, lay in the Dead Sea, swam in Galilee and even spent Christmas in Bethlehem. If you are a practising Christian don’t go to the Holy Land except for the weather. The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem is old and run down. Cheap plastic tree baubles decorate the inside. As for the stable, to reach the Grotto which is underground you have to go down a narrow flight of stairs (you would have trouble getting a dog down there) to find yourself in a room with a silver star set in the floor where the crib is supposed to have been. This is against a wall. It all resembles a fireplace. One other thing I found off-putting was that priests/monks stand around holding trays with large denomination bank notes on them – indicating donations expected but no coins. The other draw is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. This is a vast church that is serviced by Christian priests/monks. At least ten different sects live and worship here and each has its own chapel/altar. They are locked in every night at 8 pm. You can stay at a price. There is a staircase that takes you to the site of Calvary, Golgotha. It is a large room that is divided into half just by decorations on the walls and the ceiling. One half is highly decorated, the other not so much. You go to one end and the priest shows you holes in the ground where the cross stood. You go to the other side and another priest from a different sect shows you the holes where the cross stood.

at the Taj Mahal 1974

Back down on the ground the Tomb is situated no more than fifty yards from Calvary. Halfway between is a polished marble slab where Christ’s body was prepared for burial. The Tomb itself is freestanding – all in marble. The whole site has been burned to the ground on several occasions, first by the Romans who put one of their temples on it. The only thing it did was to mark the site. All of the things you are shown have been built over and over again.

As my wife and I were childless I usually worked at Christmas: one in Disneyland in California, another in Mauritius where Father Christmas arrived by speed boat. I had my shirts and other clothes made to measure in Hong Kong.

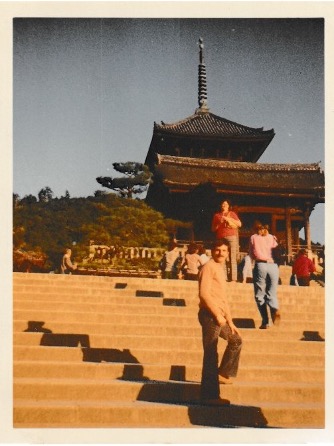

Sid at Shinto Shrine Japan

June 1974

Once, in 1980, I was sent to Nigeria, working out of Lagos on a 707 aircraft to take pilgrims to Mecca every day for two weeks. Muslims have to do it at least once in their lives. As these were very poor people their tickets had been paid by the Government. We were given a food box for each person containing half a chicken, bread, an orange and a drink. They were so unused to modern life they just dropped the bones, peel, bottle and used boxes in the aisle. You have never seen so much rubbish. We had over 200 passengers. I even had to get a man off the loo sink – he thought it was the loo. I saw the cupboard door had come open underneath so I knelt down to flip it closed. He peed all over my hand. At the other extreme I was picked to go on a month-long trip right round the world with the same wealthy passengers. As they were on holiday, we stopped every few days in another exotic place where the crew were allowed to join them in all the trips they did. Not to mention the free bar and champagne all the way round. Such a contrast to the Hadj.

Volunteers were called to go to Angola, which had just been given independence by the Portuguese. We were asked to airlift those people who needed to get out. As so often happens two different tribes were fighting for control so there was civil war. We had to land at night without lights. You could see the tracer bullets going across the runway. One local bright spark said “don’t worry, they are not aiming at you.” In the end the British Ambassador told us they were also getting out but the BA powers that be (BEA and BOAC had combined by then) told us to stay a few more days. Sod that! We were off.

PAID WORK AND VOLUNTARY WORK BEFORE AND AFTER BRITISH AIRWAYS

I retired from BA in 1990 after a couple of heart attacks. All fine now. At 80 I think I am quite fit. Once I was fit, I did a lot of charity work. I worked in one of the charity shops in Lewes but this was not for me. I went to a charity in Worthing who put us into people’s homes to look after people so their carer could take time off for a weekend or up to two weeks. I didn’t get paid but they had to feed me and paid my petrol. This stopped when funding ran out. I could never understand – not being paid and them going bust. Redundancy money was running out. I had to get a paid job so I went to work as a carer at a small children’s home. As my BA pension started in 1995, I didn’t need to work full time, so when a friend, Renee,who had a part time job cleaning people’s houses, asked me to help out I said yes. I got £5 an hour. Then we found to out to our detriment that the work got more and more. As our employer was a friend of Renee’s we did the work. We recruited another friend who had given up full time working so we would all work together and had a good time. Every year we would have a scrubber’s ball. Renee is no longer with us but together Ann and I, together with our partners still have parties though we gave up cleaning when we discovered that our boss charged £12 an hour and we got £5 between us for doing all the work.

After work, some evenings I would go to my local pub – the Oak in Station Street. Sometimes the landlady would ask me to look after the bar. Her husband had died and it was a one-woman outfit. I didn’t get any money but I would go to the chip shop after hours (11 o’clock) and we would sit in the bar with a drink and cod and chips.

While living with Aunt Carr in about 1971 I used to go out to Conyboro School in Cooksbridge. It was a school for dysfunctional kids – more like a mixed St Trinians. One boy burned down the stable block. Another pinched antique brass door furniture and sold it to antique shops. Some of the girls shinned down drainpipes at midnight and stole the school van. The keys had been left in. On the way back they hit the gatepost and were caught. The house father couldn’t understand why the bill for his cigarettes was so high. It turned out that the kids he sent to buy them had doubled the order! The children ran disciplinary meetings weekly and fined each other. Sometimes the punishment was to wear pyjamas for a week. One of my bonfire friends was working there so I started visiting him. Before long I was volunteering some evenings whenever I was able after I had done my day job.

It was at Conyboro that a new house mother came and she became my wife, Margaret, about 16 years later. She only had Wednesday off and, even then, she had to go to see her Mum in London to do her shopping and housework as she was old – over 60! I had very odd hours at work, night and day, Christmas and bank holidays but I loved my work and she, hers. She looked after the younger boys and girls. I started going to her flat for the evening. The kids would gather at the flat with us and we would teach them crafts. We also taught the gardening and took them camping at a farm in Piltdown and the New Forest. Some of these children still occasionally visit us. Tony Shephard, the Big Boys’ housefather was into raising money for different things; the biggest being a swimming pool. I have always been quite good with my hands. On my trips away I could copy things to sell: Bangkok butterfly mobiles, Indian puppets. Margaret would do soft toys. Then we would go to the shops to sell them. We also had a big fête in the summer. I was allowed one or two miniature spirits for every trip so I collected these till we had enough for a bottle stall.

Margaret loved her residential job too much to give it up and I loved my travels and had lots of family responsibities so it took us a long time to get married. When we told the owner of the school we planned to marry in 1989 he told us he had cancer and was closing the school. If we stayed in the job for three months we would get redundancy. We were married at Offham Church and organised a reception for three hundred guests. We did all the cooking and filled up the school freezers. Friends helped with the decorating and we had the use of forty beds. A coachload of the Larder family even came from Somerset! After this I was able to take Margaret on some flights using spare crew seats. We flew to the Bahamas for our “Honeymoon” and had a week paid for by BA!

Sometimes I would go to an old friend who did lots of outside catering, outside bars and holly wreaths at Christmas. He would often ask if I could help at any of these. As I loved doing things I often said yes. I did a ploughing match lunch on a local farm. I had a white coat, bow tie and wellies. The cows had been turned out of the barn. We went in and served lunch. No-one turned a hair. We did afternoon tea for God knows how many old people. It was at the hop farm in Kent. In the grounds there were deep ditches. In the running water they were full of water cress. Eric, the boss saw a money earner but how to get it? Me being small, two big blokes took a leg each and dipped me in the ditch to collect as much as I could. We had egg and cress, cheese and cress, tomato and cress and cress sandwiches! As I said, the family at Christmas made wreaths and sold them. Each year I took more and more to the cemetery. I was buying them from them. When I got to seven, I thought enough was enough and found out how to make them myself. I sold them at the boot fair in town. As usual all the money was given away. Margaret used to join me. We would do cake stalls at the Town Hall and at fêtes at the Paddock. Between us we would make about £50. We sold them cheap as we ourselves paid for the ingredients.

BONFIRE

Week before Bonfire

I have always been a Bonfire Boy – Mum joined me at aged one. I missed some due to feet problems. As I was brought up in South Street, it was their Society that I joined. I joined the committee and became hooked. Money raising was our biggest problem. We would do lots of things: Jumbles, Fêtes, Raffles, trips to London to name but a few. It was a social thing; not just one day a year. One of our team lived in Market Street and about eight of us would use his house like a social club. On Sunday evenings we would bring powdered mashed potatoes and the rest of the ingredients for a fry up.

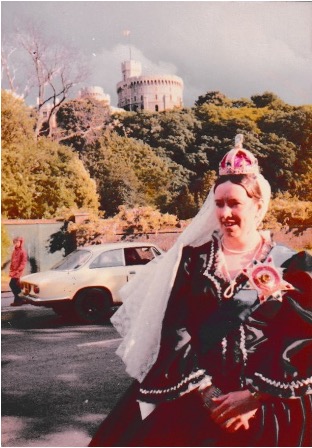

In 1977 it was the late Queen’s Silver Jubilee. The Lewes Bonfire Council was asked by Buckingham Palace if we would stage a torch light procession from Windsor Castle down the long walk to the site where the Queen would light the first of a chain of beacons round the country. The best part was the Queen would join us IN the procession. Didn’t need asking twice. We were limited to seven coaches and we had to stay in the long walk till start off time. As we were there early afternoon, we were let in the back way to the castle grounds where we were allowed to wander round the VIP area. There was a big grandstand where the band was rehearsing. We were all in our fancy dress. Margaret was Queen Victoria. When the band master saw her, he stopped them playing and had them play the National Anthem to everyone’s delight. We started to walk at about 3 pm, stopping every now and then because (a) it was along walk and (b) we had to be at a certain place where her Majesty would join in. When she did it was in an open topped jeep. At the fireside we were in the VIP part – the Royal family and the VIPs were in another grandstand. Once the fire was lit, they all came down and just mingled with us. Tony, my friend, called over to me: “God Bless you Ma’am.” Didn’t have a clue what he was talking about till a small lady standing next to me said:” Thank you” It was the Queen Mum! I was gob-smacked and struck dumb. She said a few words to me and moved on.

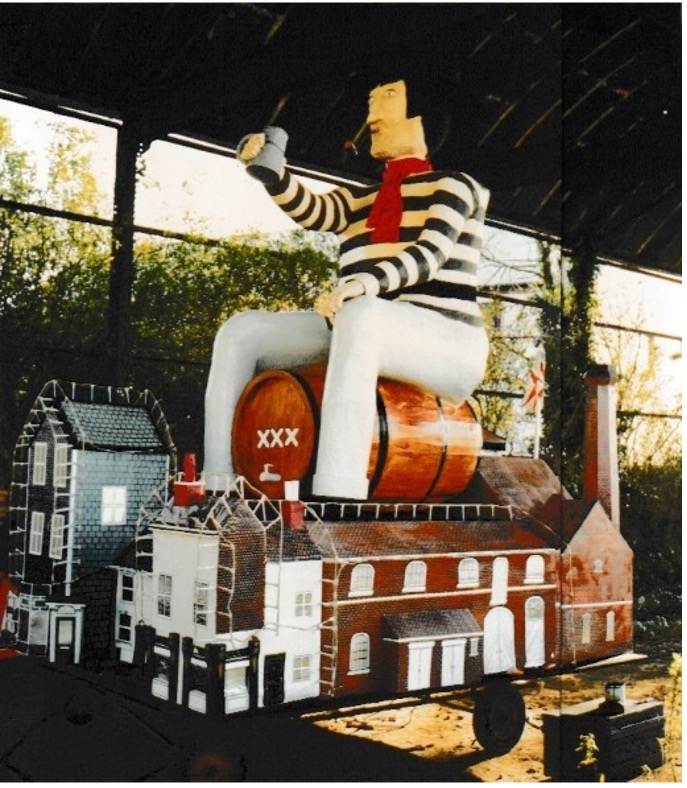

By 1979, when I was in my early thirties, I needed to be more independent, I had been living with Aunt Carr for so many years. I bought 11 Sheepfair, on the Nevill, the first house I owned. A house with a garden. The only house I looked at! My boss promised to say that my salary was enough to pay £11,000. I loved gardening and it was a good hobby to occupy me while my mates were working. I then took on the task of building the South Street fireworks. As my job was not compatible with those of other members, I said I would do it in my garage, which I did. Eric Winter asked me if I would do the Borough Bonfire fireworks as well which I did at his house. Brighton and Hove Albion had just been made up from 2nd to 1st division so I did a giant seagull with a player on his back flying between 1st and 2nd posts. In 1981 I did a Charles and Diana tribute. They had got married earlier in the year. I found out on the morning of the 5th November that she was expecting so I frantically had to knock up a stork and baby. What a lot of luck! From 1981 to 1993 I did a new set piece each year.

Six years after buying Sheepfair I moved to 16 South Way. Joan Sweatman sold me the house. She was the second wife of the original owner. I fell in love with the large garden. Joan had to remind me look at the inside of the house before I decided to buy. I sold my house on Sheepfair and moved in within a month! Another impulse buy.

CARE FOR RELATIVES

Aunt Carr had a stroke in 1983. She was paralysed down one side. As Uncle Joe was already disabled, I started my duties, caring for family and friends. I arranged that Aunt Carr’s bed was downstairs and started going there when I was home from work, doing everything. If I was going to be at work for three days I would cook three different meals, plate them up and freeze them.

I had already arranged that my other aunt would fill in for me so all she had to do was use the microwave. Uncle Joe would not let her do any cleaning so I did Aunt Ethel’s cleaning and shopping, and she did my cleaning at Sheepfair. Uncle Arch did my gardening. Work was wonderful when I explained: I was put onto what was called short haul/ long haul and was only away for a few days. This changed later when I was promoted to be a CSD (Cabin Service Director) in charge of all cabin crew on all Jumbo Jets.

Uncle Joe died in ’84. I went down as usual to find that he was not up. I went upstairs to see if he was OK. The bedroom door was locked. I broke it down to find him on the floor. He had had a massive stroke, was completely paralysed and could not speak, only move his eyes left to right. When the ambulance people came, he died. Later that day I took Aunt Carr to my house. My other aunts carried on doing the things that they were doing previously with the exception that they now came to live in my house while I was away. While at work I would like home but, on the journey back, I would think “why do I want to go home.” As soon as I walked in the door, I had to take Aunt Ethel and Uncle Arch home and usually had only two or three days before flying off somewhere else. I used two white shirts and one casual one per day so I had to wash, dry and iron enough for three days, do the shopping and cook. I didn’t mind. I just thought how much they had done for me – I could never repay them.

Aunt Carr died in ’87. Only about a year later Aunt Ethel was ill. Uncle Arch did what he could and I once again went in each day to look after them in their own home. Aunt Ethel died in ’97. I had left the airline in ’90 after 25 years living out of a suitcase. This made it easier with just Uncle Arch to look after. I wish! Tony, one of Margaret’s work-mates at the school, the big boys’ housefather, was a bachelor. When the school closed, he was homeless. He got a flat in Lewes but, as he got older, dementia set in. I became his power of attorney. We now had two people in their own homes with their own problems. I’d go down to his flat to find soap suds 12 inches deep: he would put washing-up liquid in his washing. We couldn’t keep up with cooking for everybody so arranged meals on wheels. He became a hazard to himself. I would get a call from his land lady who lived upstairs to tell me he was out in the town looking for his dog. This was at times after mid-night. He kept falling over and was taken to hospital. While he was there his landlady gave him a month’s notice to quit. When he came out of hospital he had to live with Margaret and me. I had to empty his flat, which was owned by Ann Wycherley, very quickly, and sell or dump all his possessions as I had Power of Attorney. In 2012 Uncle Arch was 99 years old and became bed-bound. His son Richard and I had to take turns living with him 24 hours a day. We did 5 days on and 5 days off. So, we then had a situation when Margaret was looking after Tony at our home and I was with Uncle Arch in his. We did it for 9 months until he died. Tony was getting worse. As his family didn’t want to know we had to put him in a home where he died in 2008.

RETIREMENT

After all this it was quite a job to adjust. I had retired and all we had to do was whatever we wanted: something that had never happened before. On our late Queen’s 50th Anniversary I was talked into baking a cake for a competition. I did a crown and won the prize. It was raffled for £60. During lock down we couldn’t raise money for Bonfire so I had the idea to take orders for baking, to be delivered when they wanted. I finished 640 mince pies, 48 meat pasties, 10 Christmas cakes, 20 holly wreaths and 36 apple turnovers. I am now in my 80th year, still healthy, and when I feel down, all I have to do is to remember so, so many good things which I have seen or done in my life. Not bad considering I was born in a slum with bad feet, missed years of education, was dyslexic. I started work in a hotel kitchen, ended as a CSD (cabin services director} on one of British Airways Jumbo Jets and in retirement I live in a large detached house in South Way.

Sid Larder © 2024

Edited by Ann Holmes with thanks to Krystyna Weinstein